Jetocetes and Relatives

One of the evolutionary spectacles unique to Snaiad is the presence of jet-propelled advanced “vertebrates” in its rivers and seas. While underwater jet propulsion is observed in a lot of small creatures on Earth and other planets, Snaiad’s Jetocetes are the only known case where this method of locomotion has evolved in large animals that descended from terrestrial ancestors.

Needless to say, this adaptation entails a series of drastic alterations to the traditional “two-headed” Snaiadi bodyplan. Most prominent among these changes is the splitting of the second-head digestive tract into a separate canal devoted to propulsion, and the re-routing the section that handles the food into the first head, where the genital-sheath jaws, uniquely in Snaiad’s natural history, act as true mouthparts.

While such extreme modifications seem impossible to have evolved naturally, certain animals that still survive today give us clues about the transformation of swamp-dwelling swimmers into the jet-propelled masters of the sea, -and beyond.

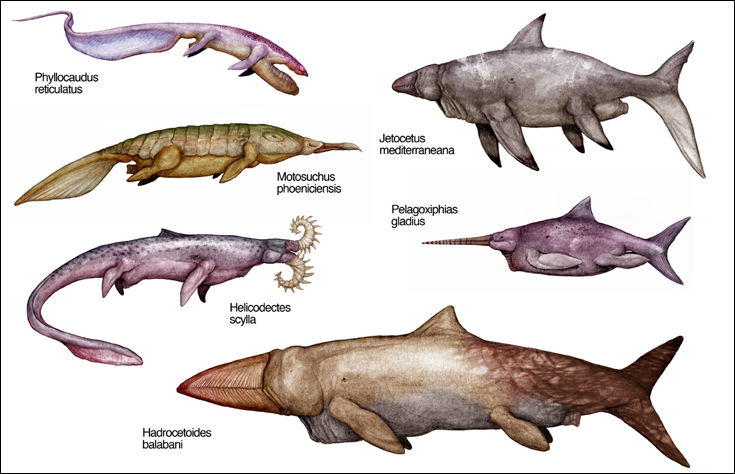

Species: Phyllocaudus reticulatus

Common Name: Reticulated Leaftail.

Size: 90 centimeters or less from snout to tail.

Habitat: Rivers and tributaries in the Azonic Jungle.

This species, along with the closely related P. flagellurus, belong to the most basal group of jet-propelled swimmers. The Reticulated Oartail is found only in the Azonic river system, feeding on vegetation and small river animals. It swims generally with the help of its muscular tail and paddle-shaped fins, but when cornered it can rapidly eject water from its anal sphincter for sudden bursts of speed. Unlike its cousin groups, Phyllocaudids do not have a differentiated tract of their digestive systems adapted exclusively for jet propulsion; they merely swallow and expel water rapidly. Neither is this a preferable way of locomotion for the Phyllocaudids, since they void all of their stomach contents while jetting and go hungry as a result. These living fossils are very rare, and research suggests that their numbers are declining. Captive breeding programs are underway to protect them from extinction.

Species: Motosuchus phoeniciensis

Common Names: Eyeing Scooter-Croc, Armadillodile.

Size: Up to 2.5 meters long.

Habitat: The Scoptic Delta in Lower Vesterna.

Large rivers on almost any continent of Snaiad are patrolled by Motosuchid jet-crocodiles; swimming in eerie stillness they purr along on their gastro-intestinal water jets. Ancient and cryptic, these creatures represent an intermediary branch on the way to truly marine jet-swimmers. The Motosuchid digestive track has split partly into two; one branch handling food and a blank tube providing propulsion. Still, they cannot drink saltwater and their jet engines aren’t efficient enough to provide constant propulsion. For this reason they are confined to rivers and isolated lakes, but they have adapted to this limited niche expertly; 40-million year old fossils of the first Motosuchids are often difficult to tell apart from modern species.

The Eyeing Scooter-Croc, native to the Scoptic Delta, gets its name from the staring dorsal eye spots that bear a passing resemblance to the ship decorations of the ancient, distant Earth. Its hooked beak is suitable both for digging along the bottom sediment, or sharp lunges at unwary prey. Its distended jet-gut can produce intense five-second power bursts to rocket the animal towards its terrestrial victims, who usually never get to realize what hit them.

Species: Helicodectes scylla

Common Name: None.

Size: Up to 4 meters long.

Habitat: Continental shelves and reef gardens around Midland

When first caught off the Sea of Midland fifty years ago, this creature dropped into the world of Snaiadi zoology like a bomb. Nobody could understand exactly what it was, and how it used its bizarre, ram’s horn jaws that suspiciously looked like the Helicoprion fossils of the distant Earth. Investigations in the next few decades have fortunately shed more light on the lifestyle and the origins of this mystifying creature.

Initially thought to be an aberrant Motosuchid, Helicodectes was found out to be a specialized Jetocete that had secondarily lost its torpedo-shaped body shape and tuned down its jet gut to pursue a specialized lifestyle; feeding on the many species of Sea Serpents (Ophicarida,) found on Snaiadi reef gardens. Helicodectes has been observed patrolling slowly along the reefs, using its tail rather than jet gut to propel itself. Its bizarre jaws make up a perfect tool to snag the ribbon-like bodies of Sea Serpents.

Even after revealing its mysteries, however, Helicodectes reminds us that Snaiad is still an alien place, rife with discoveries, weirdness and wonder.

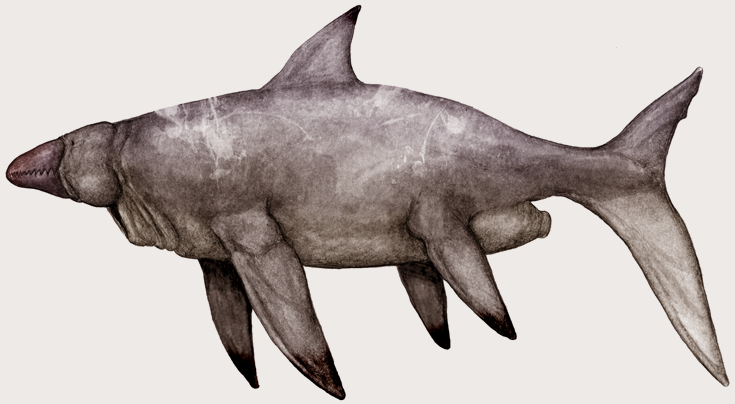

Species: Jetocetus mediterraneana

Common Names: Jetshark, Neomed Jetshark, Neo.

Size: 2 meters long.

Habitat: The Neomediterranean, sometimes seen outside in the Sea of Aar as well.

True Jetocetes bear more derived jet-propulsion systems than either the Phyllocaudids or the Motosuchids, but not the heart-like pumps of the Cardiocetes. Part of their digestive system has completely budded off from the main line, turning into a jet pump that can provide continuous flow. The other half of the digestive tract has fused into the jaws on the first head. This way, true Jetocetes (and their descendants, the Cardiocetes,) can actually eat with their first heads, an unusual condition found in no other lineage on the planet.

Although the terrifying Polycardiac Cardiocetes give them no quarter on the open ocean, many ordinary Jetocetes still occupy medium-to-large predator niches in shallow waters and reef gardens. The Mediterranean Jetshark is a typical example. Possibly a subspecies of the virtually identical Aarite Jetshark (J. aaritas,) it dwells in the Neomediterranean year-round, feeding on anything smaller than itself. Although attacks on humans have been very rare, public beaches on the Neomed regularly post Jetshark alerts to warn bathers during crowded days, just to be on the safe side.

Species: Pelagoxiphias gladius

Common Name: Swordpinguin.

Size: 1.5 meters excluding beak.

Habitat: All across the oceans of the Southern Hemisphere.

Distributed all around Snaiadi oceans, the thirty-plus species of Thalassoxiphid “Swordfish” are as fast as true Jetocetes can get. These creatures all have egg-shaped, compact bodies housing well-developed water jets, but no heart-pumps like the Cardiocetes. Strangely, they have well-developed rear fins that seem out-of-place on streamlined swimmers, but these limbs actually serve to vector their water jets in tight angles for increased maneuverability.

While it would seem that Thalassoxiphid Jetocetes would be at a disadvantage when competing with the extremely fast Polycardiac Cardiocetes, the two groups manage to exist side-by-side in most marine ecosystems. The Cardiocetes prefer more energy-rich prey with their supercharged metabolisms, leaving a selection of less nutritious prey items to the Thalassoxiphids, who can live on them since they don’t regularly risk starvation when fueling their water jets. Thalassoxiphids and their faster descendants thus manage to live in the same places by exploiting different kinds of prey.

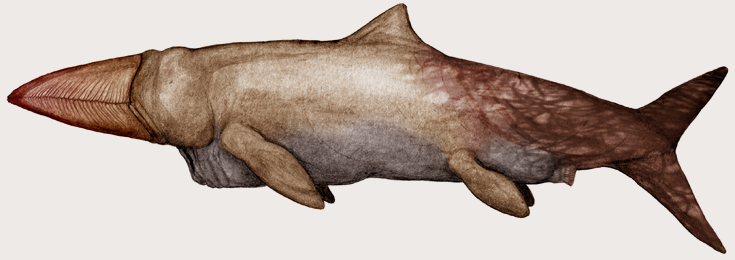

Species: Hadrocetoides balabani

Common Name: None.

Size: 6-7 meters long.

Habitat: All across the Great Northern Ocean, sometimes found in warmer seas as well.

While the Cardiocetes have some of the largest filter-feeding species on Snaiad, old-school Balenarhynchid Jetocetes such as Hadrocetoides actually enjoy larger species diversity and biomass, especially in the cold climates. These creatures vary in size from just over two meters to thirteen meters long, and ply the Snaiadi seas for plankton and pelagic swimmers of all kinds.

Protected from the cold in deep layers of blubber, Hadrocetoides balabani can be regularly observed around the Great Northern Ocean. They travel in family pods of up to a hundred individuals, and in turn are hunted by the two species of vicious Torpedichthyid Polycardiac Cardiocetes that live across their range.

Copyright laws protect all intellectual property associated with Snaiad.

All artwork, concepts and names associated with this project belong to C. M. Kosemen, unless otherwise stated.