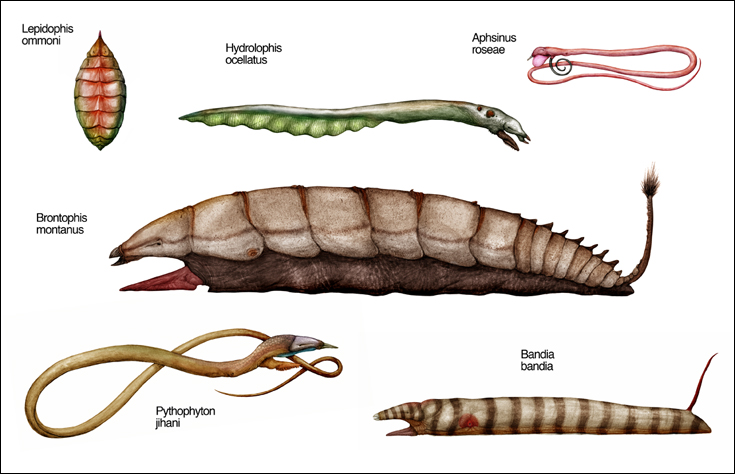

Lophophids

Serpentine body shapes are far more common on Snaiad than other worlds. However, most of Snaiad’s varied “snakes” are small-to-medium sized creatures that usually feed on smaller animals. The Lophophids form an exception to both of these trends by being predominantly herbivorous, and also quite large-bodied. Their elongated bodies contain long, fermenting guts that can deal with even the toughest plant matter. Their second heads, decked out with rasping teeth, can likewise cope with a wide variety of vegetation. These features, and the Lophophids’ ability to prosper on a limited diet of sprog, make these giant, snake-like organisms some of the most common large herbivores, especially on warmer climates.

Species: Bandia bandia

Common Name: Bandy-bandy.

Size: 2 meters long.

Habitat: Pansavannah.

This is a typical Lophophid with no legs, powerful, rippling “walking” muscles on its underbelly and a rasping second-head that works like a lawn –or sprog- mower. Like many other Lophophids, Bandia lives in small family groups and is usually active in broad daylight. One would think that these creatures would be extremely vulnerable to predation as slow-moving, fat masses of meat, but they have a very interesting defense technique to keep predators at bay. Occasionally these animals, like many other Lophophid species, raid the nests of colonial trikes (Acridasteria,) and eat as many as they can of the small, toxic invertebrates. When this behavior was first observed, it was thought that Lophophids lived like anteaters of Earth, even earning a related Lophophid genus the name Myrmecophis (Ant-snake.) Actually, the Acirdasterian trikes form an extremely limited part of the Lophophid diet, but the Lophophids somehow extract the invertebrates’ potent poison and store it in their bodies. Any predator foolish enough to eat such a creature thus risks a nasty episode of poisoning that will usually not kill, but severely traumatize it. To make this danger clearer, many Lophophids like Bandia have distinct, startling color schemes on their bodies.

Bandia bandia is commercially valuable on Snaiad for its attractively patterned leather and interesting body chemistry, which has potential even for human scientists. Natural hunting of these animals is forbidden and all products come from captive-reared farm herds.

Species: Brontophis montanus

Common Name: Tractorsnake.

Size: Up to 7 meters long.

Habitat: Sprogland, pinnacle ranges and scrubland on Lower Vesterna.

While some Lophophids rely on their poisonous flesh for defense, others have developed enormous sizes and thick body armor to resist predators. Such giant forms also enjoy a wider distribution than their poisonous cousins, since their ranges are not constrained by the distribution of nest-building Acridasterians that they use to distill their poison.

Endlessly mopping up sprog, “grass,” small shrubs and every other type of vegetation like living combine harvesters; these giants are the largest of the Ankylophid Lophophidians. Unlike their smaller cousins, they are more active in the night, spending the days in thickets or in the bases of vegetative pinnacles in pinnacle ranges. Their presence is noticeable the next morning by the deep furrows they leave across the landscape, twisting and turning like gigantic exercises of calligraphy. Not surprisingly, these traces were thought to be “alien Nazca lines” during the first aerial surveys of Vesterna. Later research confirmed the true nature of these lines and as of now, no intelligent species are known from Snaiad. (The only possible exceptions are the mysterious “Stone Axers” that are known only from their 30-million year old fossil tools.)

Species: Phytophyton jihani

Common Names: Blue python, Jihan’s sidewinder.

Size: Up to 5 meters long.

Habitat: A variety of habitats in Isterna, ranging from the Sovanian Pinnacle Range in the north and the edges of the Ankyranian Desert.

Not all Lophophids are heavy-set crawlers with muscular traction pads along their bellies. A great majority of Lophophid species are active undulators that move with a lateral waving motion of their bodies. Such species, classified as Sigmophidian Lophophids, can also swim or climb, and are able to exploit more niches.

Phytophyton jihani is one such generalist, present in a numerous different habitats across its widespread range. Where it can, Phytophyton utilizes the poisons of Acridasterians to defend itself, but in many other places it simply relies on its cryptic shape to hide itself from danger. When cornered, these creatures start trashing about, flailing their tails and bodies insanely to drive their attackers away. Despite their large size, they are also one of the fastest Lophophids, and can achieve surprising bursts of speed using a unique, oversized sidewinding action.

Species: Hydrolophis ocellatus

Common Name: River Snake, Eyed Snake.

Size: 3 meters long, usually smaller.

Habitat: The Scoptic River in Vesterna.

These mysterious and highly secretive aquatic Sigmophidian Lophophids are known only from a dozen specimens and twice as many blurry underwater photos. They feed on the vegetation that grows along the river bottom and sometimes beach themselves, apparently in order to bask in the sun. Although its purely aquatic lifestyle seems highly specialized, Hydrolophis is thought to be a recent descendant of other Sigmophidians like Phytophyton.

Almost every year, expeditions are launched into the Scoptic River delta to find out more about this enigmatic creature.

Species: Aphsinus roseae

Common Name: Pink Dandysnake.

Size: 90-100 cm long.

Habitat: The Great Azonic Jungle, in Southwestern Vesterna.

While the great Ankylophidians and fabulously patterned Bandiaformes get all the attention, two out of three Lophophid species belong to the diverse-but-humble subgroup of Florophidians. All Florophidians are small-bodied, more-or-less snake like herbivores, although several species feed on small animals and even blood (Vampyrophis sp.) Quite conspicuously, they all lack the muscular “crawling pad” found in the larger Lophophids. These animals can be found in a variety of habitats; including sproglands, scrublands, deserts, forests and pinnacle ranges. Although their body shapes are conservative, Florophidian species in different habitats show diverse specializations for their respective niches.

The climax of Florophidian diversity can be observed in the jungles in western Vesterna. Many species of Dandysnakes like Aphsinus abound in this region, usually in such a variety that individuals from three or four different species can be found living together on a single tree. Aphsinus roseae, named for its pink, rose-like color, usually lives just below the canopy layer, feeding on leaves and “fruit”. The males have a highly developed throat flap that they use for sexual displays.

Species: Lepidophis ommoni

Common Names: Tree Scab, Emerald Scab, Aphidsnake.

Size: 7 to 10 centimeters long.

Habitat: On tree-like plants in the Great Western Pinnacle Range and surrounding areas.

On Snaiad, the equivalents of trees sometimes have fleshy, thick, bark-like growths that they shed seasonally in a way comparable to Earthly plants shedding their leaves. Numerous creatures have evolved to take advantage of these nutrient resources, and this bizarre group of Lophophids (Chitonophidia,) is also among their ranks. Lephidophis is a characteristic member of this group, with a tough series of plate-like scales down its back, a rasping second head completely hidden under its body and a very strong, muscular traction pad along its belly that makes it difficult to remove from the bark. Masses of them can usually be seen in infected trees, glimmering in the upper branches like a set of parasitic sequins. Despite their conspicuous color, almost no animals except from certain specialized predators disturb them. This is because Lepidophis and relatives, like their Bandiaform ancestors, can synthesize an irritating poison from the juices of the plant they feed on.

Quite interestingly among Snaiadi “vertebrates,” Lepidophis and most other Chitonophidians consist of all-female populations, able to give birth without the need of males, or mating. This makes them especially populous, but at the same time, vulnerable to disease and other maladies. Consequently, the populations of many Chitonophidians follow irregular boom-and-bust cycles.

Copyright laws protect all intellectual property associated with Snaiad.

All artwork, concepts and names associated with this project belong to C. M. Kosemen, unless otherwise stated.