"Polydactyls"

This is generic the name given to a variety of separate “vertebrate” animal groups that are united by the presence of multiple digits on their front and rear limbs. These digits are thought to be derived from the multitudinous, centipede-like tube-limbs of even earlier “vertebrate” ancestors. As the tube-like feet merged and bundled over the course of Snaiadi “vertebrate” evolution, some took the role of fluid-filled hydraulic muscles, others became bone-like support structures or degraded into more conventional fibrous muscles, and yet others protruded from the tips of extremities like digits. As the majority of large Snaiadi land animals have two digits per limb, a trend towards reducing these digits and incorporating them inside the arms and legs must have taken place as more “advanced vertebrates” evolved from Polydactyls or Polydactyl-like ancestors.

Today, the different Polydactyl groups occupy a number of low-key niches all over the planet. Although most of these are fairly small and unremarkable animals, fossil evidence indicates that certain lineages, now extinct, grew to megafaunal sizes far earlier in the planet’s natural history. The unusual Turtiformes might also be Polydactyls.

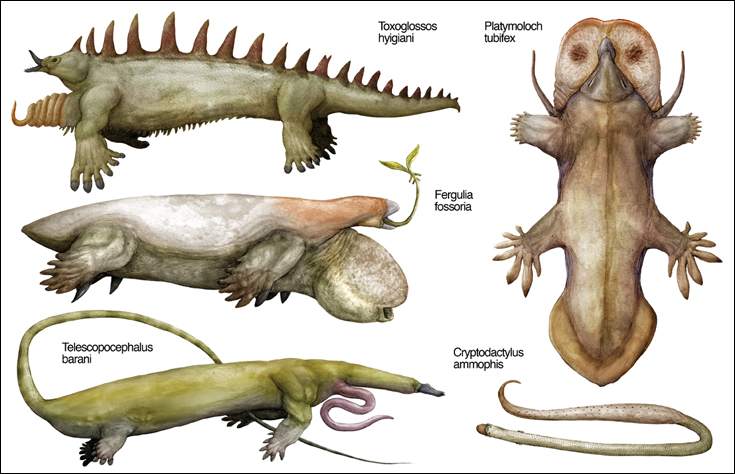

Species: Telescopocephalus barani

Common Names: Whizzard, Telescope Whipslider.

Size: 40-50 centimeters long excluding tail.

Habitat: Rugose scrubland between the East Isternan plains and the Great Isternan Pinnacle Range.

Telescopocephalus is one of the three thousand species of widespread Whipsliders (Tunicasaurs) found all over Snaiad except Thalassia, Aar and the Endland. In form as well as function these creatures can be considered to be Snaiadi lizard-analogues, although several other lineages have evolved similar body shapes and lifestyles on Snaiad. These animals come in a variety of sizes and shapes, but all Tunicasaurs are characterized by the presence of multiple toes, (although limbs are reduced in some groups,) long, tentacle-like second heads and peculiar extensions of their hydraulic muscles into their body walls, which allow them to wriggle through the undergrowth with ease.

Telescopocephalus belongs to a sub-group of Tunicasaurs called the Lygocephalans, also known as Stickheads. These animals are usually active at day, and use their elongated, probe-like heads to break into the nests of colonial Trikes. In night, they rest under pinnacles or specially-dug burrows. Telescopocephalus is so far the largest Lygocephalan known, with a body exceeding half a meter in size. Its long, whip-like tail, usually twice as long, works as a predator-distracting lure and in males, as an ornament of sexual competition.

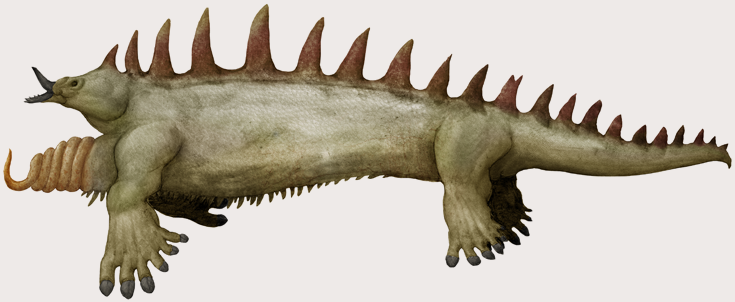

Species: Toxoglossos hyigiani

Common Names: Bukalemun, Ridge Chameleon.

Size: 20-25 centimeters long.

Habitat: Vesternian Pinnacle Range and surrounding areas.

Classified by some researchers as Tunicasaurs and by others in a group entirely of their own, the nine or ten species of Toxoglossos show a remarkable convergent evolution with Flagelloglossid Jos and Chameleons of Earth. They have a spring-like, hyper-extensible second head which they use to “zap” their arboreal prey. Unlike Jos, but like Earthly Chameleons, they also have a form of active camouflage and social display under their skin, but with Toxoglossoans this means a shape-changing ability rather than a color-changing one. Muscular extensions of their skin, running along their back, flanks and vents, have the ability to “pinch out” and mold themselves to a variety of silhouette-breaking shapes. Since numerous Snaiadi predators seem to be color-blind, it is thought that a shape-shifting ability has been more useful than a color-changing one in the hectic world of the pinnacle ranges. These animals move in a very unusual, inchworm-like fashion, grasping branches with one pair of legs and reaching out with the other.

Species: Fergulia fossoria

Common Name: Chunker.

Size: 20 to 40 centimeters long

Habitat: Plains and sprogland in Lower Vesterna.

Probably the closest Polydactyls group to the well-known Turtiformes, the little-known Ferguliids are an obscure lineage adapted extensively for digging and herbivory. They have ridiculously muscular second heads for their size, similar (but not related) to those of the great herbivores. These organs are furnished with plant-grinding surfaces and circular “chewing” muscles that run around their circumferences, and can cope with any plant material, hard or soft, green or red.

Ferguliids burrow underground, but mostly in sprog, continually eating as they burrow. In some cases, they have been documented to “eat their way” into the upper stories of dense tree pinnacles at pinnacle ranges.

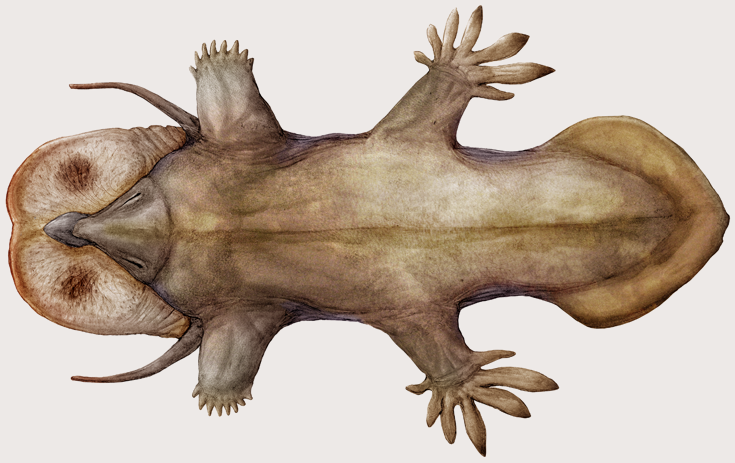

Species: Platymoloch tubifex.

Common Names: Flapjack, Eyed Flapjack.

Size: 30-40 centimeters, usually less.

Habitat: River Sambatyon and other fresh-water bodies in Oroland, related species present on south Isternan coasts.

The sub-continent of Oroland, isolated as an island for most of its geological history, still houses numerous groups of unique animals. Among them are the Tubibrachids, unusual Polydactyls adapted extensively to a freshwater existence. Flattened along river or pond bottoms, these animals’ entire lives are spent underwater, although they can hibernate under mud or manage a pitiful crawl on land if waters dry up. Unique among Snaiadi vertebrates, these animals have tube-like snorkels extending out from their “armpits,” connecting to the lungs inside. Thanks to these organs, Tubibrachids do not even need to surface for breathing, although even the snorkels are seldom used because they absorb the majority of their aquatic oxygen directly from their guts, “inhaled” by their second-heads.

Tubibrachids like Platymoloch are peaceful creatures, dragging their flattened second heads hoover-like across the bottom sediment to scoop up any small animals, plants or organic detritus. Although they are not very active, they can swim away in a surprisingly fast, “waving” motion if danger threatens. These animals can survive for very long, and are also one of the “living fossils” of Snaiad. Eighty million year old fossil Tubibrachids like Echinodesmus and Platytitanis are not much different from their contemporary descendants, except perhaps in their size.

Species: Cryptodactylus ammophis

Common Name: No common name.

Size: Up to 18 centimeters long.

Habitat: Beneath sand dunes or steppe-soil in central Thalassia.

Cryptodactylus shows the unusually common example of “snaking;” the reduction of arms and legs that has happened countless times in widely different Snaiadi animal groups. By itself Cryptodactylus is a little known and probably boring creature, digging tunnels under sandy soil to hunt burrowers like itself. However, this animal’s identity as a Polydactyl, as shown by the scale-like fingers and toes embedded in its body wall, bears witness to the enormous diversity and old age of this group. Present on every continent on Snaiad, Polydactyls must have diversified very early on in the planet’s history.

Cryptodactylus belongs to a unique group of burrowing, legless Polydactyls (Punctatophids,) found only on Thalassia. Some species are very abundant and are staple foods for the various species of Mikados.

Copyright laws protect all intellectual property associated with Snaiad.

All artwork, concepts and names associated with this project belong to C. M. Kosemen, unless otherwise stated.