Tromobrachids

This group bears yet another set of extraordinary adaptations that elicit the popular phrase, “it could only happen in Thalassia.” Fusing their second heads with their “sternums” and front limbs, Tromobrachids have evolved the strongest jaw-equivalents in all of Snaiad; stronger even than the hydraulic bites of the Kahydroniformes, with the advantage of being able to bite, chew and swallow from the same “mouth”. Not involved with feeding anymore, their first heads have become thin, periscope-like organs useful only for observation, grooming and breeding. Fast, large and powerful, the only thing stopping the Tromobrachids’ complete takeover of predatory niches on Snaiad has been the isolated location of Thalassia. Despite these advantages, their evolutionary confinement in the island continent has led to a very low species count for this group, not more than seven according to the latest data. Unusual aquatic Tromobrachids are known from the fossil record.

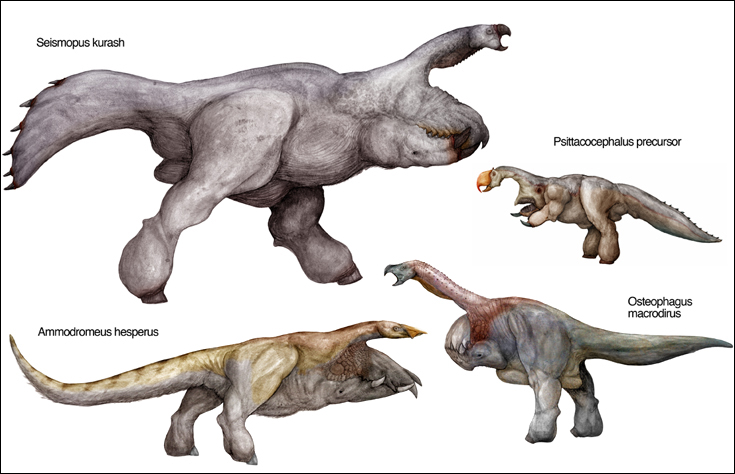

Species: Seismopus kurash

Common Name: See Rex

Size: 9 meters long.

Habitat: All across Thalassia.

Weighing well over a ton, this giant is easily one of the biggest predators in all of Snaiad. It regularly hunts large Titans and herbivorous Monoanticherans, and has even been observed killing (but not eating,) predatory Volugnaths almost as large as itself.

Beneath its fame as the largest predator on Thalassia, Seismopus is a pretty ordinary Tromobrachid, with its arms melded together into muscular, crushing jaws. Although quite sturdy, its arm-jaws still retain limited sideways movement and can open up to “embrace” large prey items. Two nostrils on each side of its arms give the disquieting illusion of eyes, and are also responsible for Seismopus’ famous, sonorous stereo roar. The first head bears a well-developed throat pouch that females use to carry their hard-shelled, boxy eggs around. In males, a huge, flag-like genital folds up into the same space.

Species: Ammodromeus hesperus

Common Name: Sandrunner.

Size: 3-6 meters long.

Habitat: Interior regions of Thalassia.

This smaller Tromobrachid prowls the hot interior of Thalassia, feeding on Pistonopodid Bounderjaws and snake-eating Mikados. Ammodromeus is a pursuit predator and relentlessly runs after its prey, eventually exhausting it. Although individuals have been observed grouping together to chase down larger prey, this behavior is a simple result of intersecting interests rather than any genuine pack behavior.

These animals have a number of unusual characteristics that make them stand out among Tromobrachids. These include a shaggy coat of enlarged “hair,” a very short neck, hyper-extended chest keels and moveable claw “teeth” in their arm-jaws. They have the anomalous habit of swallowing their prey in a single bite, “walking” the dead body into their cavernous mouths with their claw-teeth. After eating, they usually rest for several days before getting up to run again. “Vomit piles” containing the indigestible hard parts of their prey are a common sign of Ammodromeus in the Thalassian interior. There are two species of Ammodromeus, one of which is smaller and brighter colored than the other.

Species: Osteophagus macrodirus

Common Names: Graboid, Stinkfowl.

Size: Up to 3 meters long.

Habitat: Thalassian plains and forests.

While some Tromobrachids like Ammodromeus have mobile and extensible arm-jaws, this species has its arms fused into solid, bone-like jaws. Furthermore, the hydraulic muscles that close their arms are buttressed straight against the ventral skid, using the whole body’s support for extra power. Not surprisingly, Osteophagus has the strongest “bite” (or in the Tromobrachids’ case, hug,) in all of Snaiad, easily enough to crack open and consume bones. These animals spend most of their lives as scavengers, using their long, periscope-like first heads to spot kill sites and rotting carcasses on the Thalassian plains. They have also been observed accompanying larger Tromobrachids on hunts, waiting patiently for them to finish eating and then moving in to feast on the leftovers. Another favorite food source is Ammodromeus “vomit piles”, which are eaten with a special relish. However, scavenging alone is not enough to support these animals and they frequently supplement their diet with small Bounderjaw species or thick-shelled Thalassiochelid Cannonballs, which they crack open like nuts.

Their fetid diet gives Osteocephalus’ a deadly array of contagious microorganisms breeding around their arm-jaws, which they practically use like venom for hunting or defense. Sometimes, however, even they catch infections and fall sick. Such individuals have been observed crunching Erythrophyte wood, perhaps for its medicinal properties.

Species: Psittacocephalus precursor

Common Name: None.

Size: 2-4 meters long.

Habitat: Ur-thalassia.

A hint to how this amazing group evolved can be found on the island of Ur-thalassia, which lies right next to the Thalassian mainland. Extremely rare and its population concentrated in a precious few valleys, Psittacocephalus feeds on small animals it captures by smothering them into its chest-based second-head mouth, which is surrounded by small, teeth-like projections and a primitive version of the upper jaw keel that is so prominent in more “advanced” Tromobrachids. While it has no proper arm-jaws, Psittacocephalus can still use its free-swinging arms like jaws by pressing them against its chest area.

Despite its archaic characteristics, this animal also bears a number of unique adaptations that mark it off as a sideline rather than an ancestor. Its head bears a very large, brightly colored beak that males knock together in competitions of sexual prowess. The legs and feet, while superficially similar to those of other Tromobrachids, nevertheless have a unique construction. For these reasons, Psittacocephalus is classified all by itself in the Protobrachid clade; a sister group to all other Tromobrachids.

Copyright laws protect all intellectual property associated with Snaiad.

All artwork, concepts and names associated with this project belong to C. M. Kosemen, unless otherwise stated.