C. M. Kosemen

Artist and Researcher

***

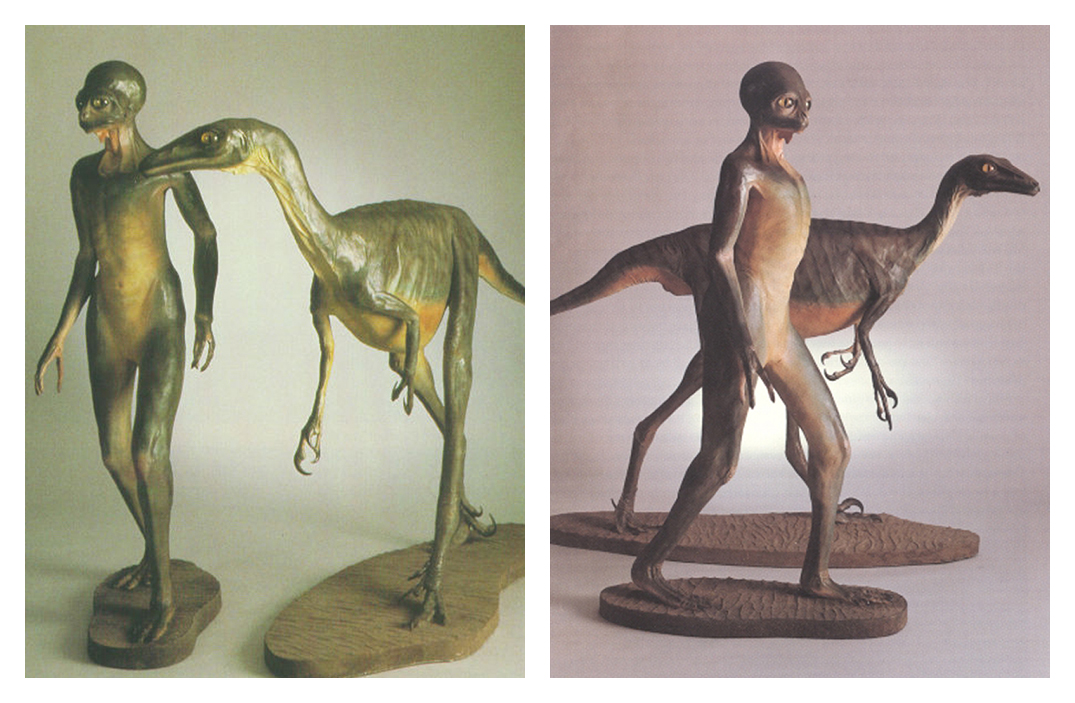

A world of dinosauroids (with Simon Roy)

There are two highly-popular, vexing questions about dinosaurs: What would the world look like if these strange and majestic animals had not gone extinct? And, would they ever evolve into intelligent species comparable to humans? In 1982, palaeontologist Dale Russell, after observing "... a general trend toward larger relative brain size in terrestrial vertebrates through geologic time, and the energetic efficiency of an upright posture in slow-moving, bipedal animals", postulated the Dinosauroid, a humanoid, erect-gaited sophont which may have evolved from Troodon-like dinosaurs had the end-Cretaceous extinction not occurred.

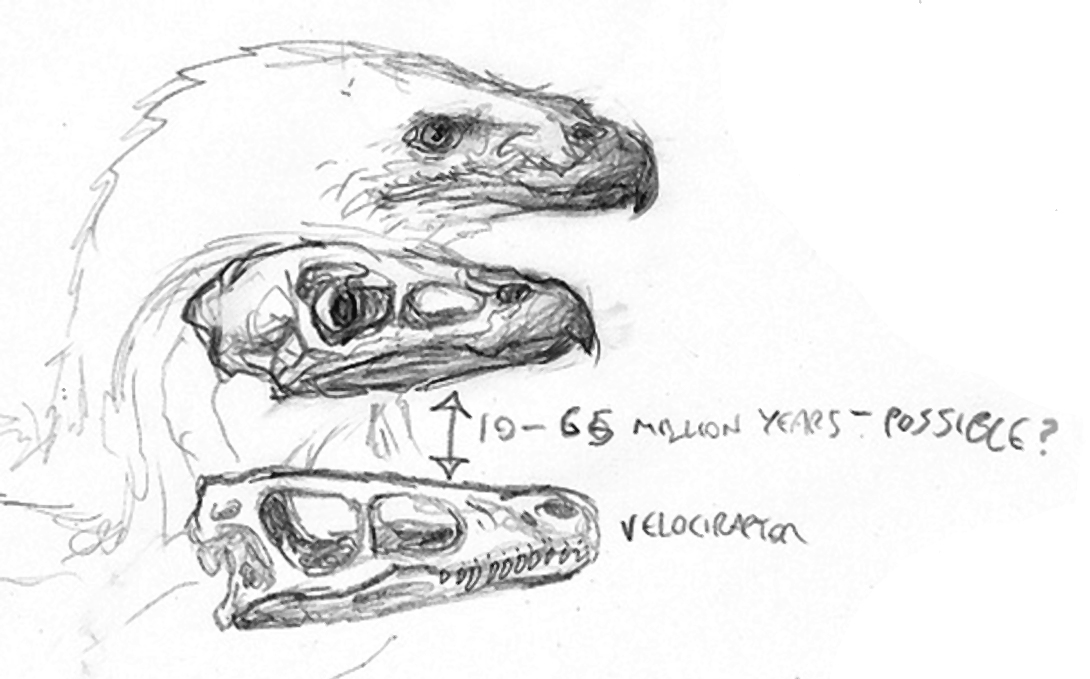

This question occupied the minds of yours truly (seen here on the right), and world-building comic genius Simon Roy (on the left), as well. We were unconvinced by Russell's Dinosauroid. We thought that an erect, humanoid sophont was too prejudiced towards humans to be realistic. We were instead inspired by zoologist Darren Naish's writings on the evolution of intelligent, bird-like dinosaurs: "No, post-Cretaceous maniraptorans wouldn’t end up looking like scaly tridactyl plantigrade humanoids with erect tailless bodies. They would be decked out with feathers and brightly coloured skin ornaments; have nice normal horizontal bodies and digitigrade feet; long, hard, powerful jaws; stride around on the savannah kicking the shit out of little mammals; and in the evenings they would stand together in the trees, booming out a duet of du du du-du, a deep noise that would reverberate for miles around..."

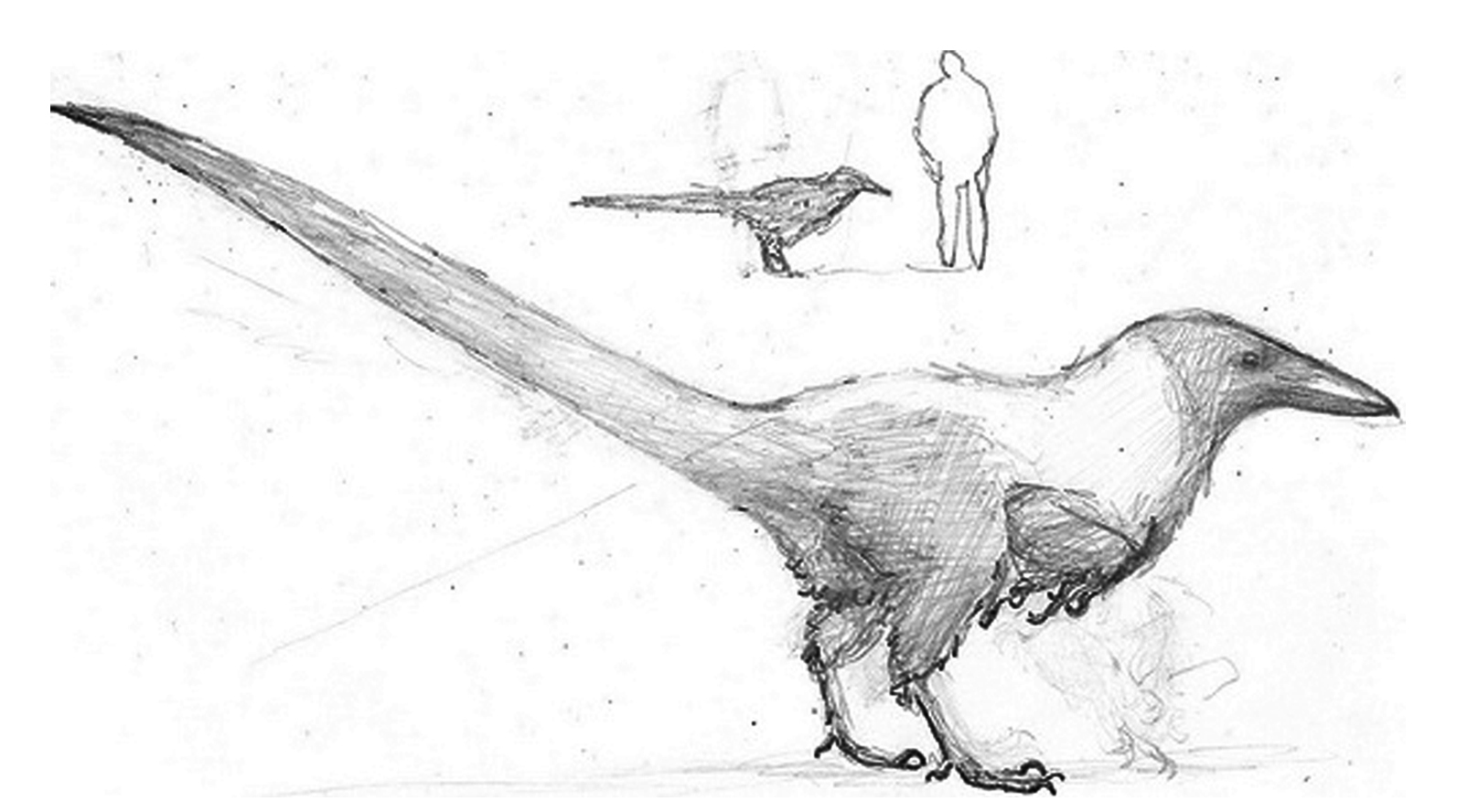

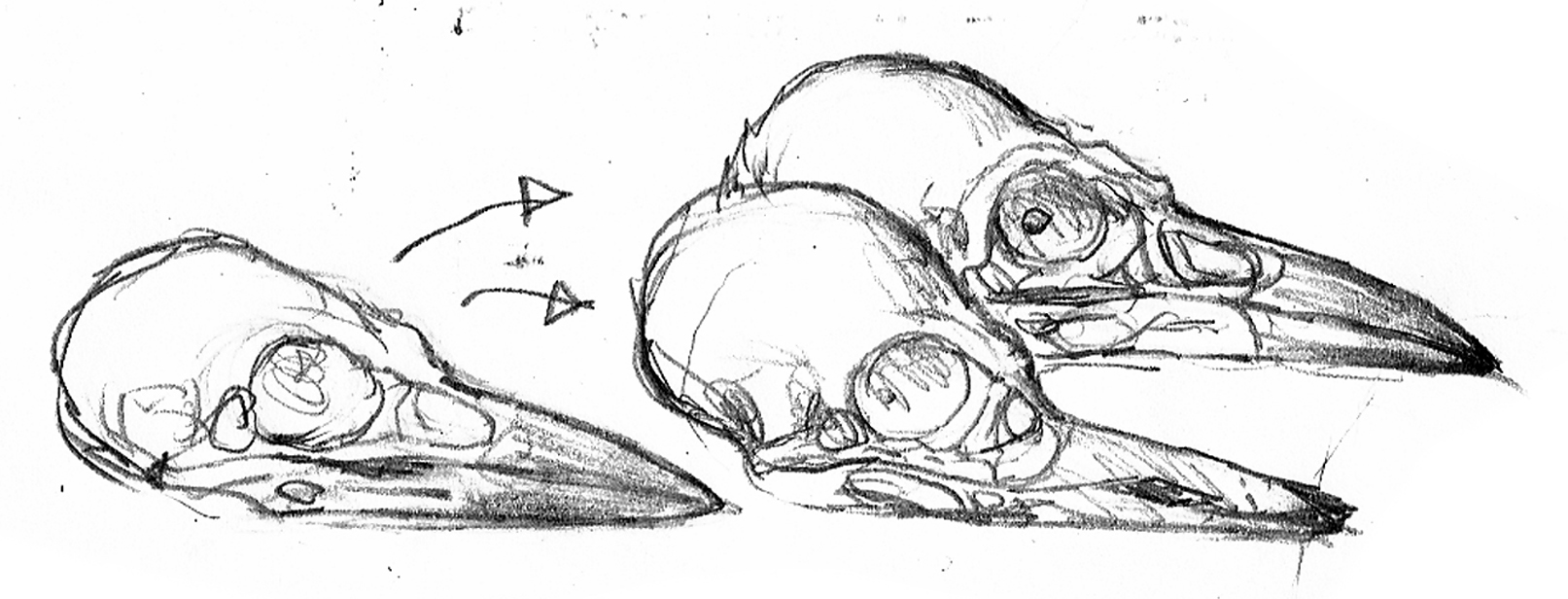

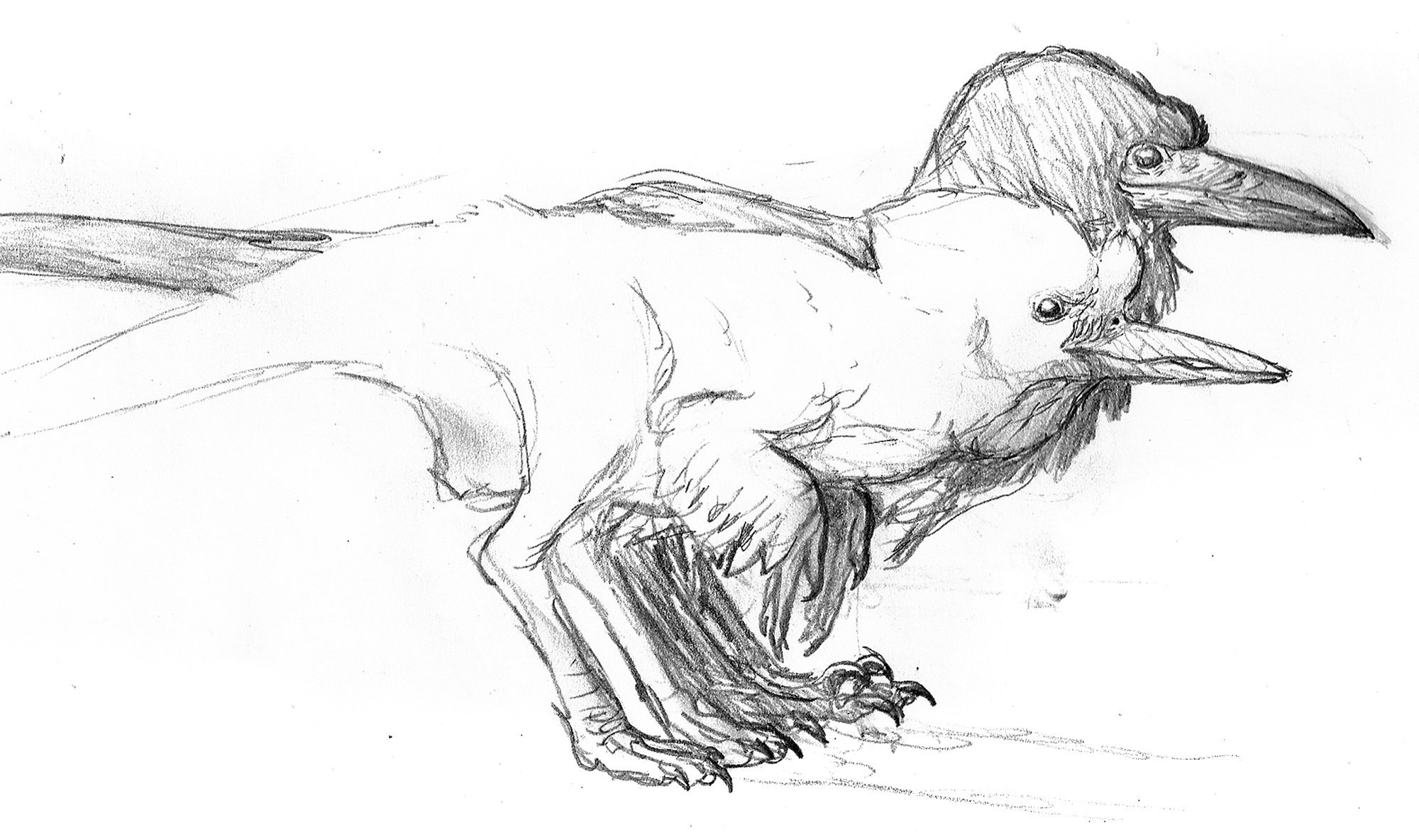

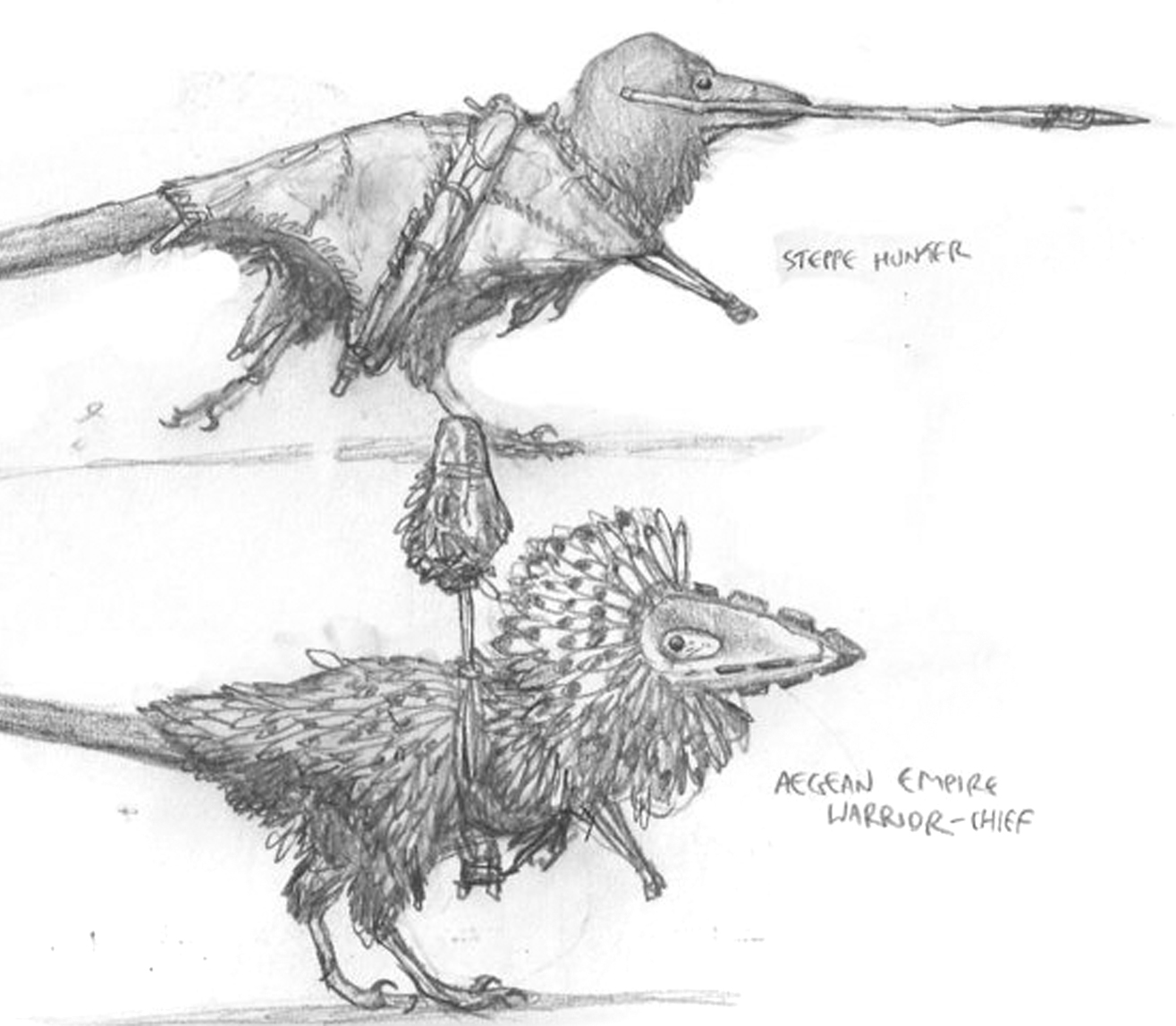

Towards the end of the '00s, Simon Roy and I independently began to develop our concepts for bird-like intelligent dinosaurs. Inspired by the ravens he saw around his Canadian home, Simon drew the corvid-like dinosauroids seen above.

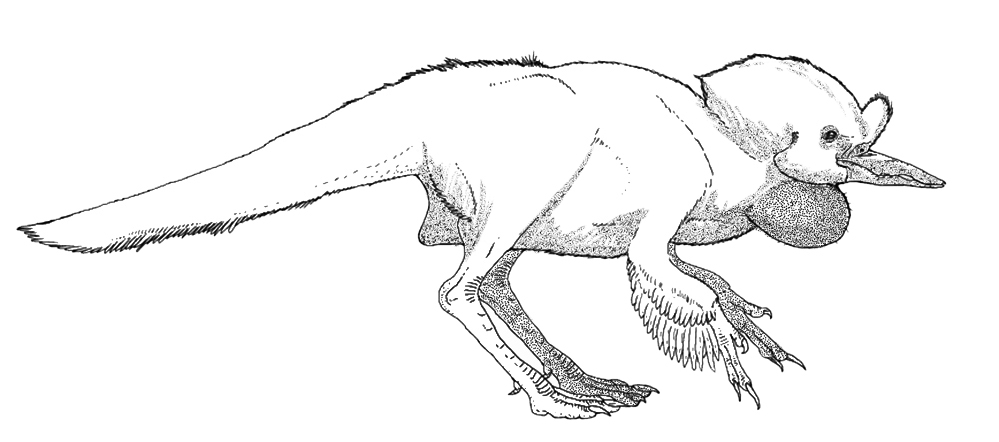

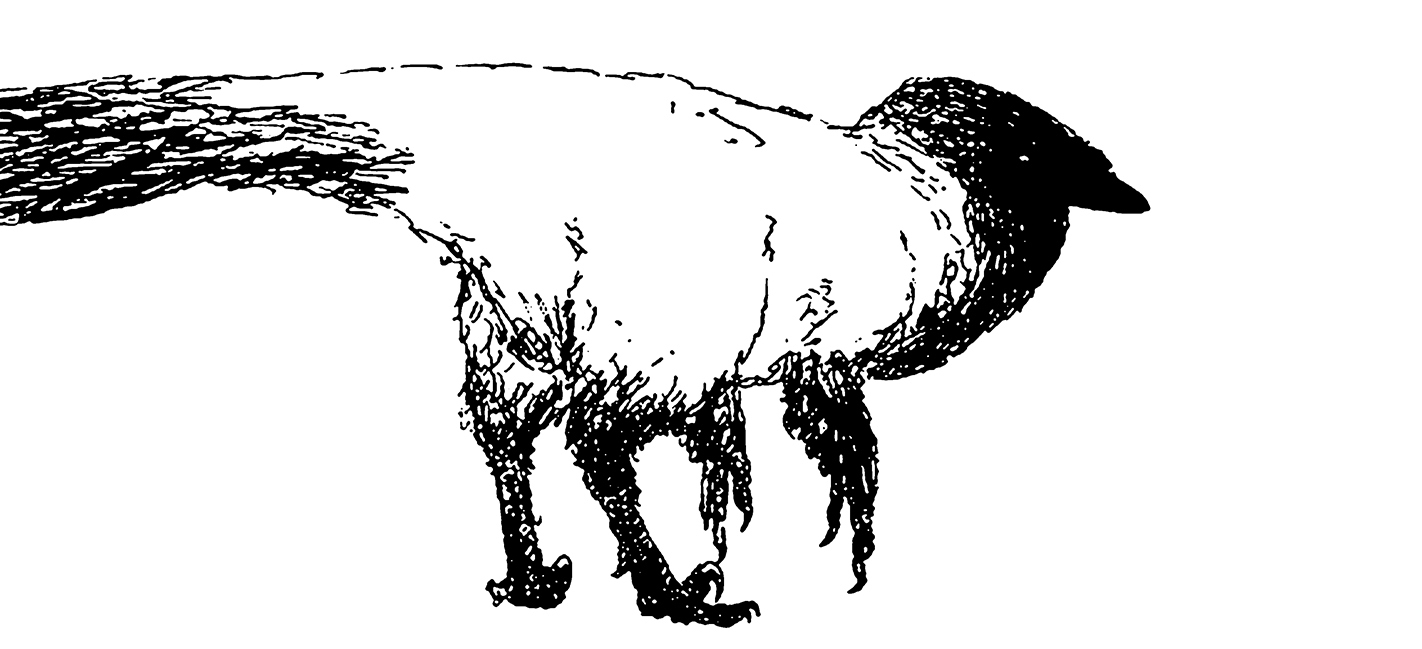

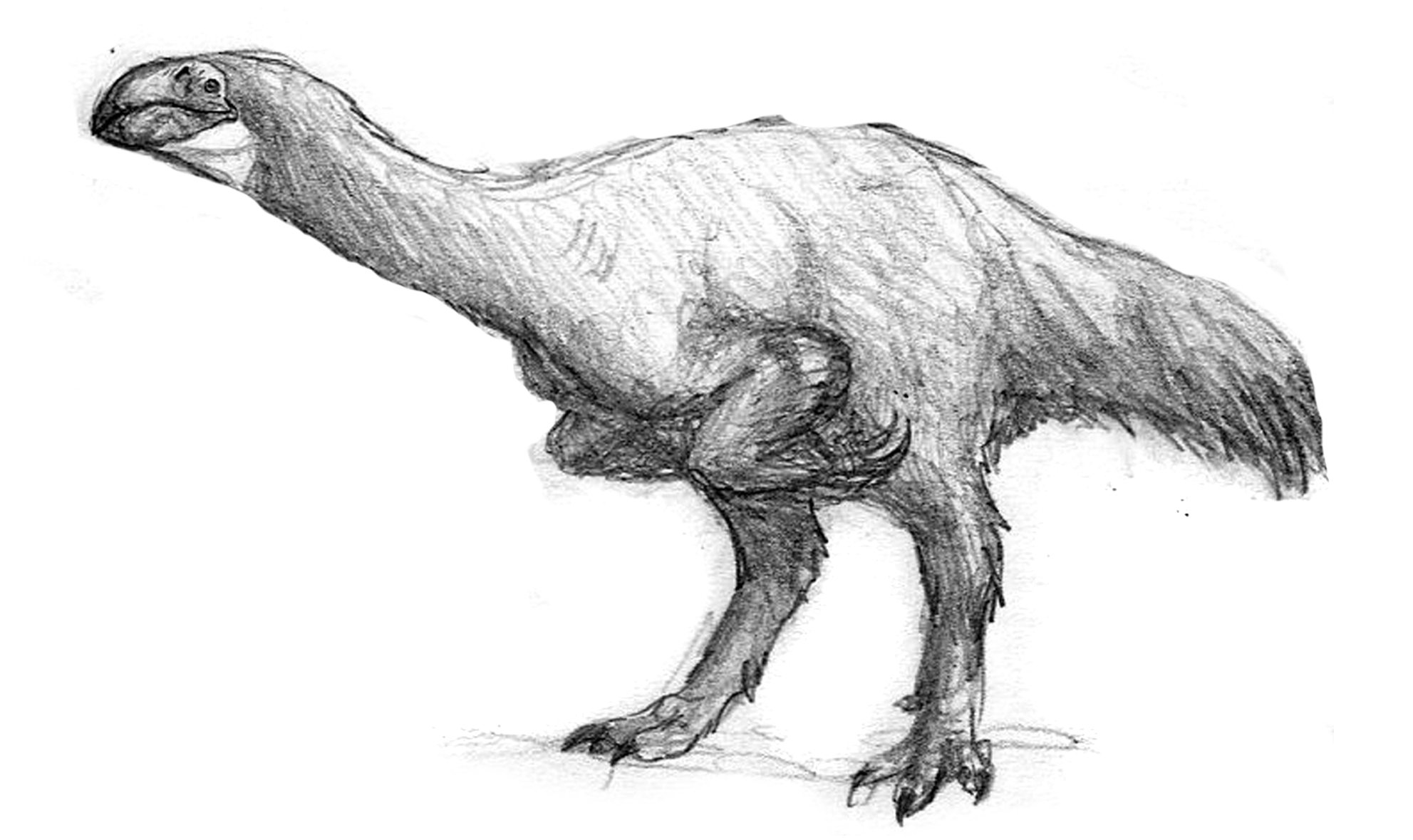

I, in turn, was inspired by ground hornbills, parrots, certain dinosaurs and corvids, and came up with the speculative organism seen above. I named it Avisapiens saurotheos.

Simon and I soon got in touch with each other; and started developing a world and a storyline for our dinosauroids. Our collaborative efforts continued, on-and-off, until the mid-2010s. Our aim was to develop the Dinosauroids story into an illustrated story-book, which we naively hoped to sell to a major sci-fi publisher. But we soon realised that we enjoyed world-building more than writing a story, or putting a book together. We kept bouncing concepts back and forth, but never had a chance to publish them, until now. Most of the body of work you see on this page was drawn by Simon, based on ideas we created together. I also contributed some of the "cave drawings" and certain creature illustrations. This is the first time the totality of our Dinosauroids-universe works has been displayed online.

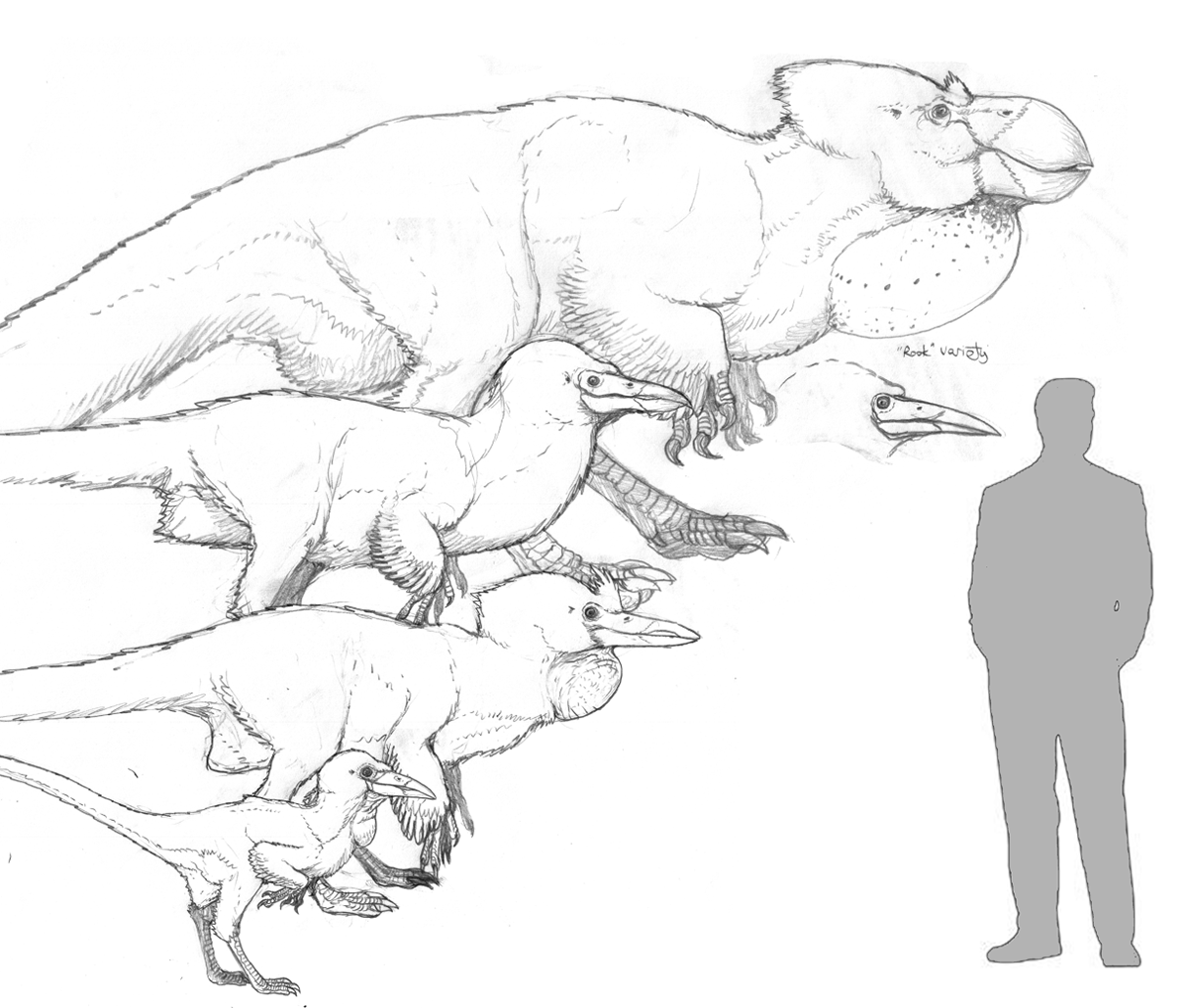

Simon and I refined the design of my original Avisapiens dinosauroid...

And created a few more sentient races to accompany them. There was one more, slightly-crow-like species of Avisapiens (a continuation of Simon's corvid dinosauroids - Avisapiens tataricus). These two species were joined by a variety of "forest giants" (Gigantosapiens borealis), and a race of pygmies (Avisapiens minimus).

Simon's refined studies of corvid-like, and pygmy dinosauroids.

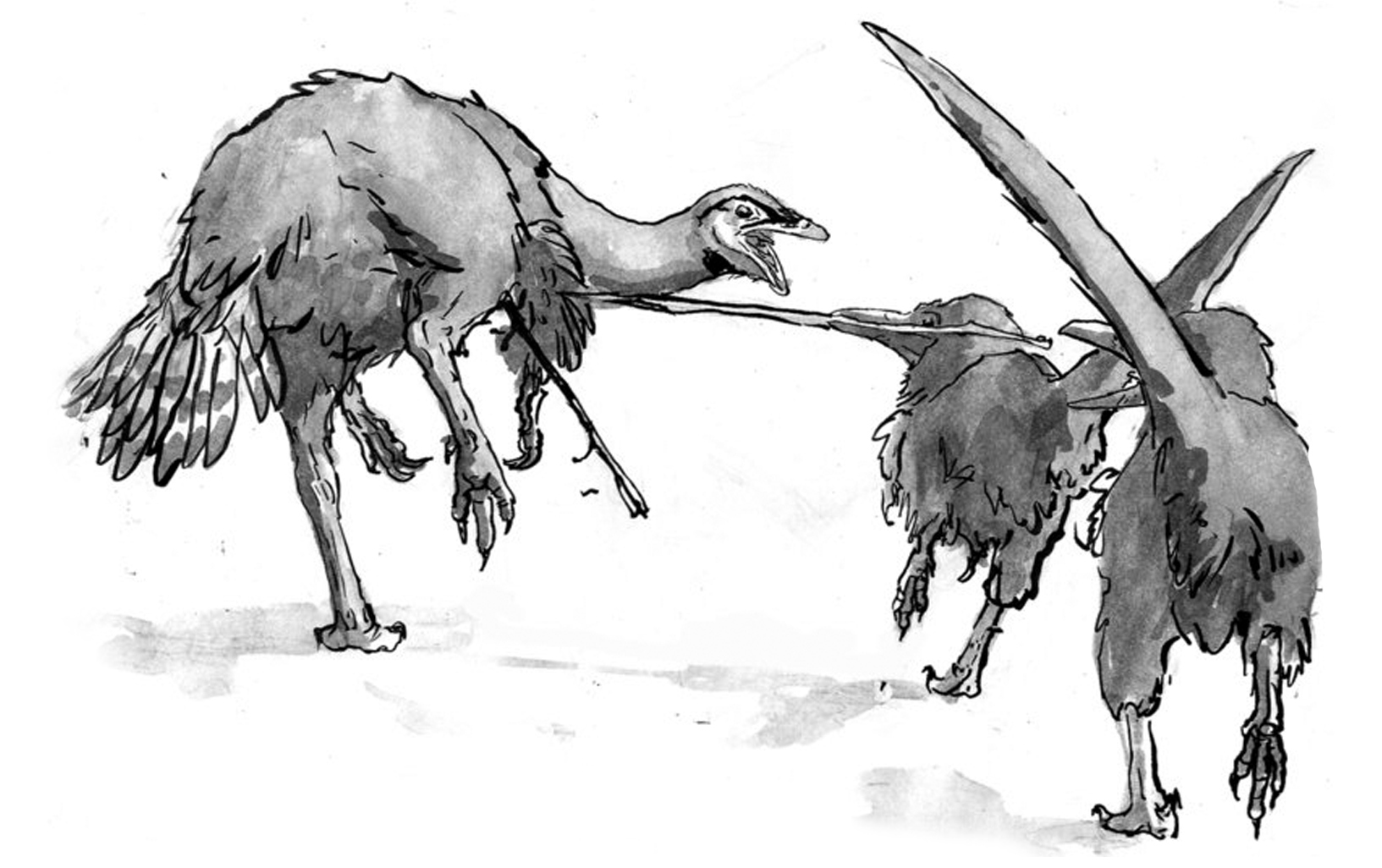

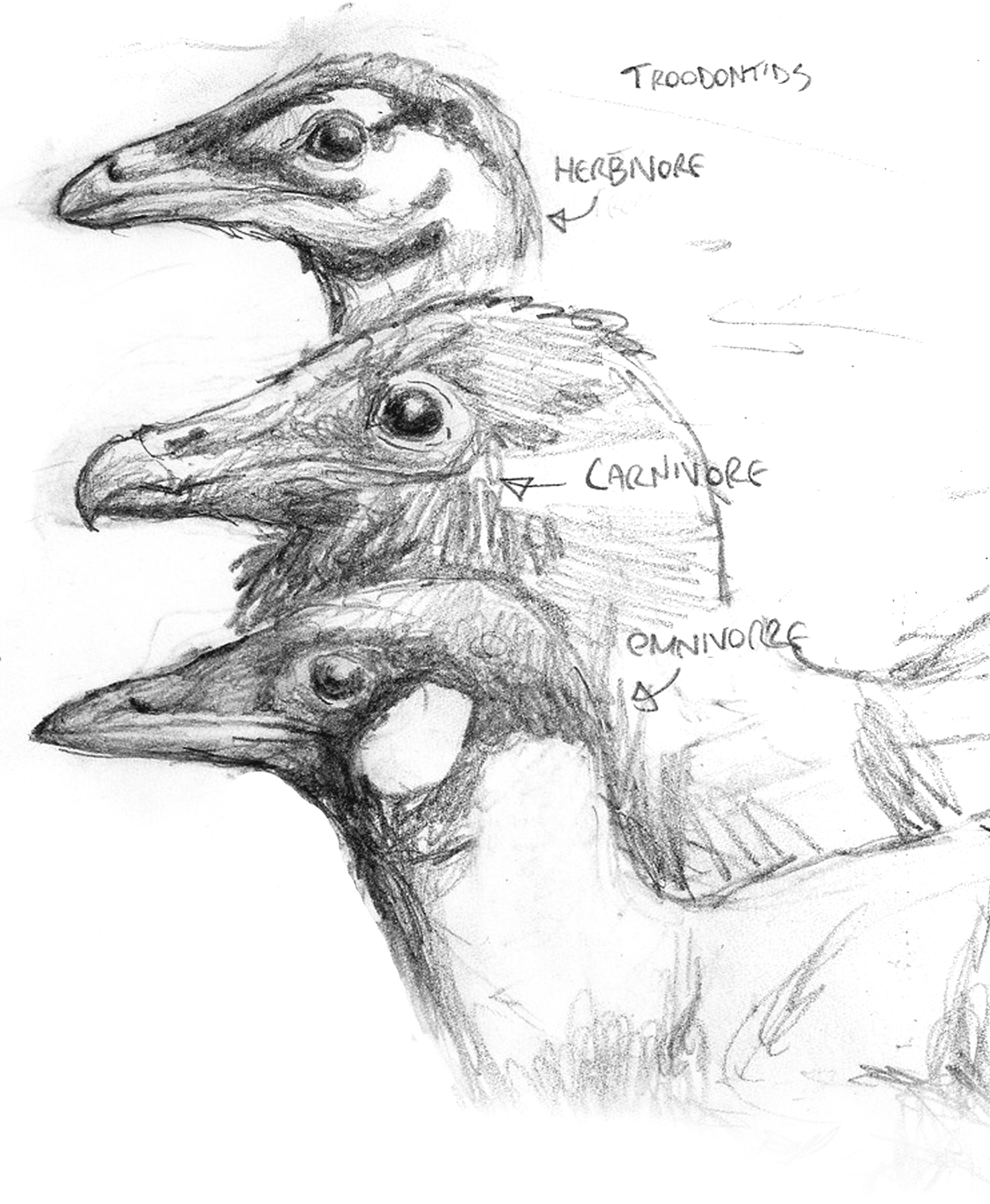

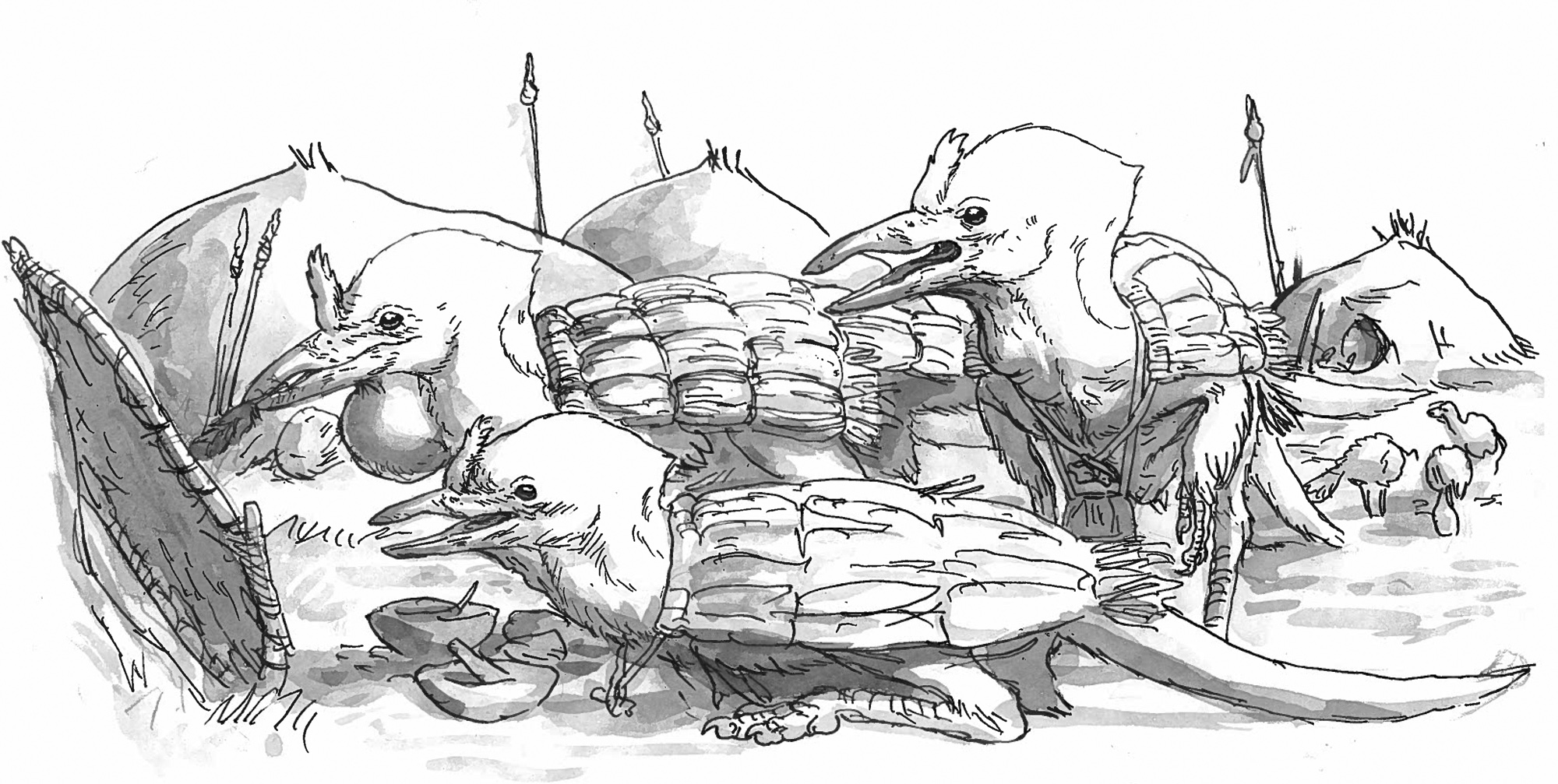

We also designed an extensive selection of animals around our dinosauroids. We predicted that even without the K/T mass extinction, dinosaurs and other animals would have kept on evolving, and many "familiar" groups of dinosaurs would have gone extinct. We thus designed a world where the majority of surviving dinosaurs were the descendants of "maniraptoran" groups; birds, deinonychosaur ("raptor") dinosaurs, troodonts, oviraptors and therizinosaurs. Here, you can see two boreal dinosauroids using mouth-spears to hunt herbivorous troodont quarry.

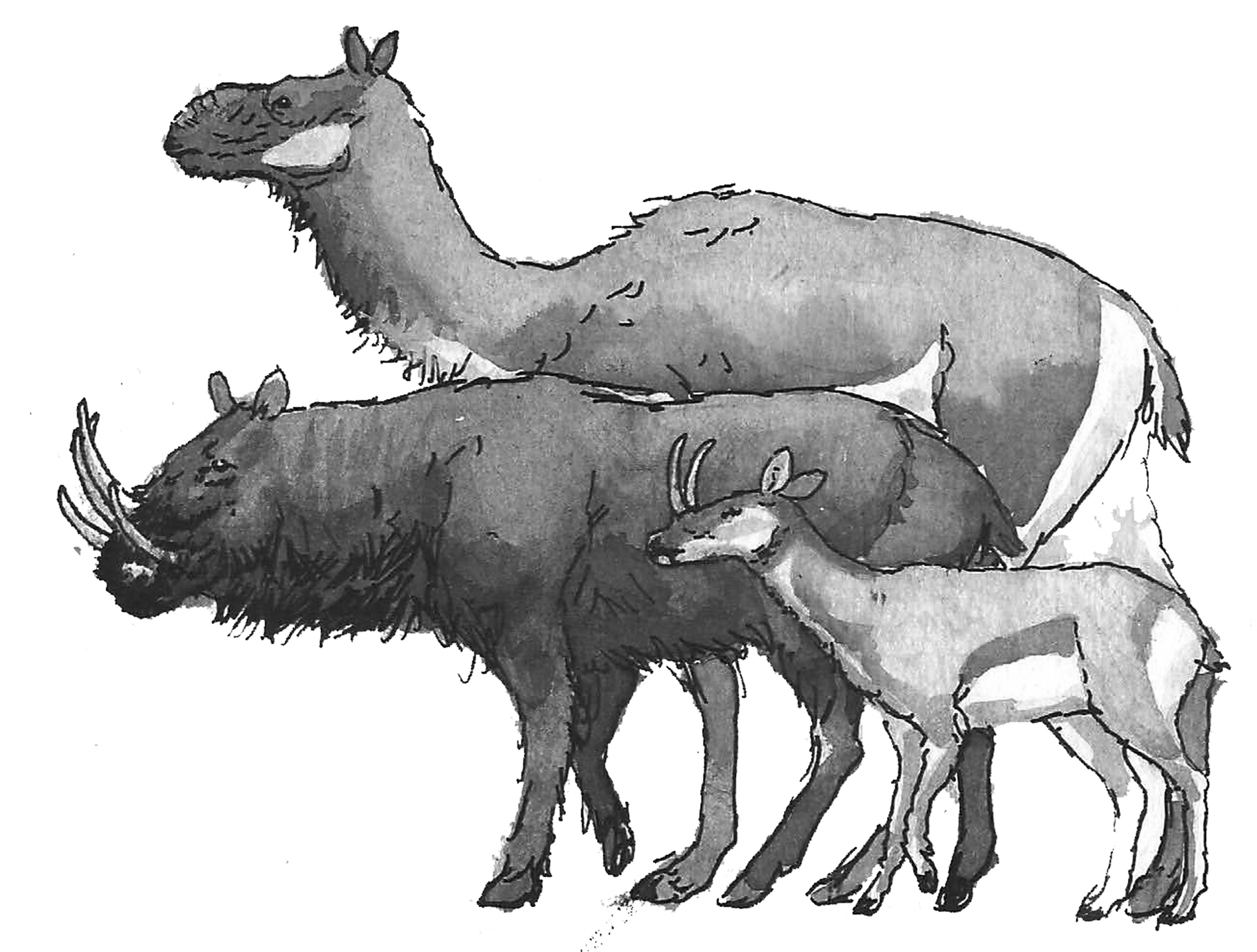

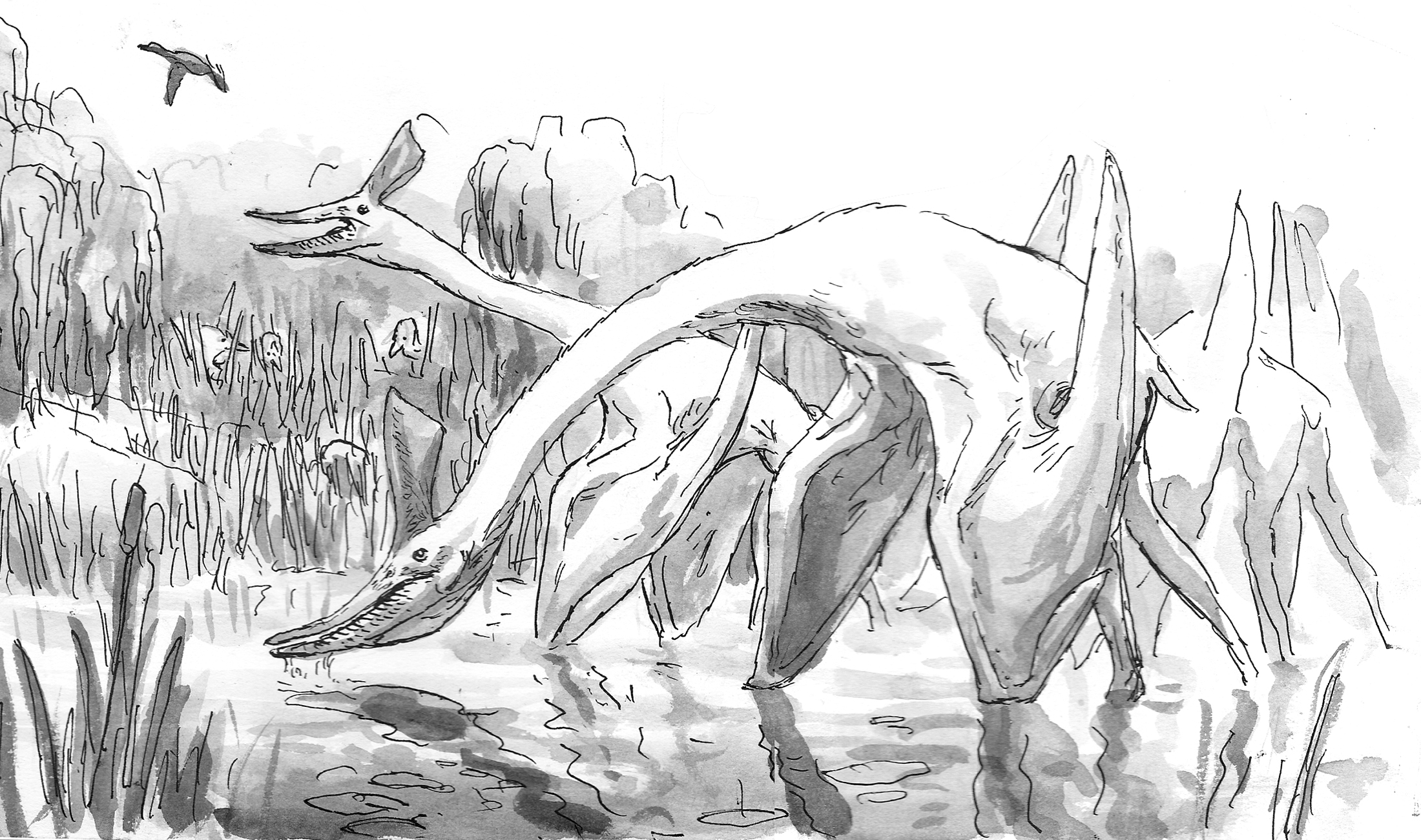

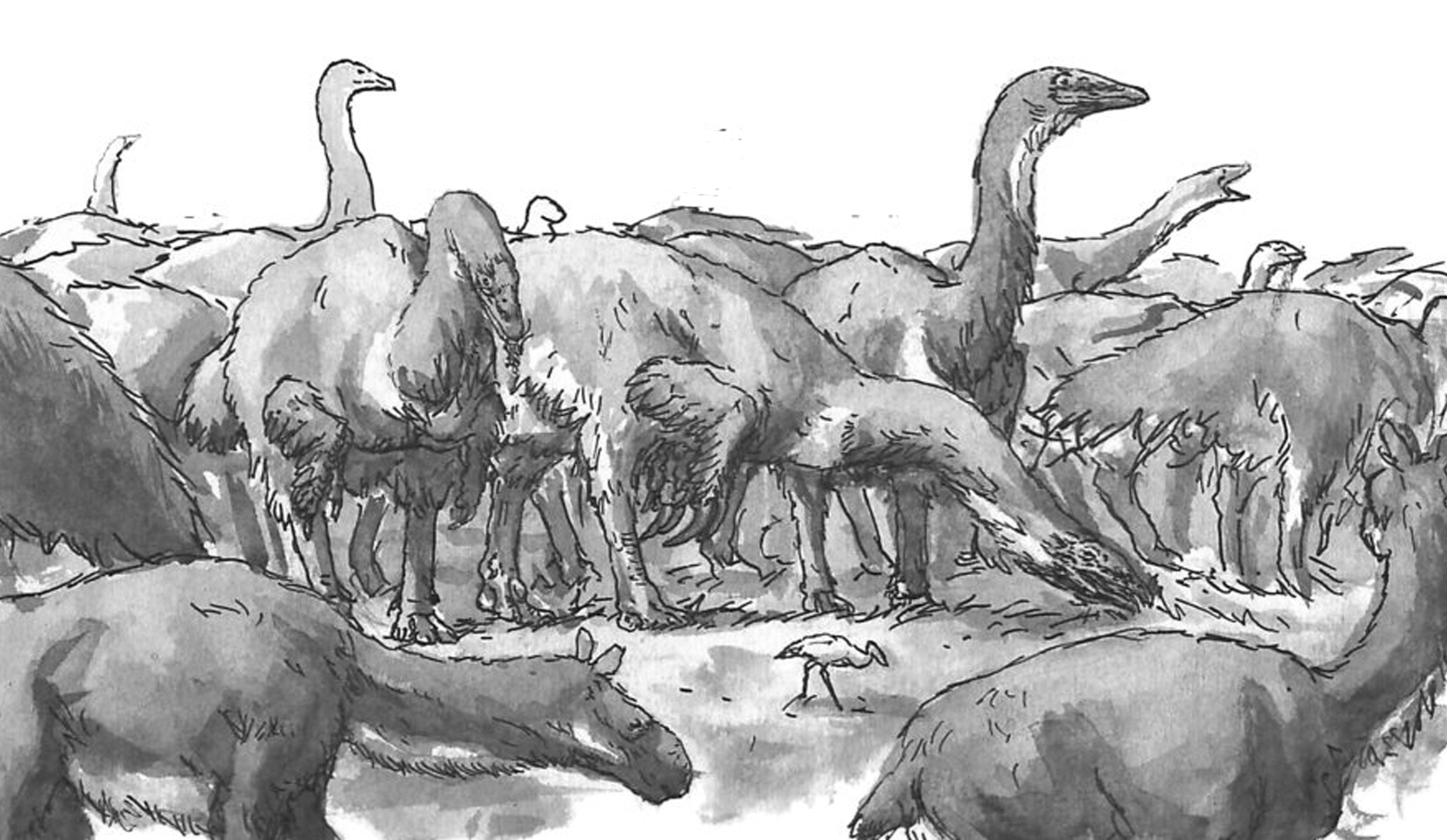

We also did not want this world to be devoid of mammals. Even during the age of dinosaurs, certain mammals evolved into large and sophisticated forms. We envisioned a world where parallel groups of mammals, similar to, but phylogenetically distinct from today's forms, co-evolved alongside the dinosaurs during their continued reign. The scene above shows an Eurasian water-hole crowded with two species of ornithomimid herbivores (Rugocursor, left-centre; and Cyanogularia, far right); alongside robust (Afrotuberculocamelus) and gracile (Odontocervoides) species of herbivorous mammals which, for the lack of a better term, we decided to name "supermaras".

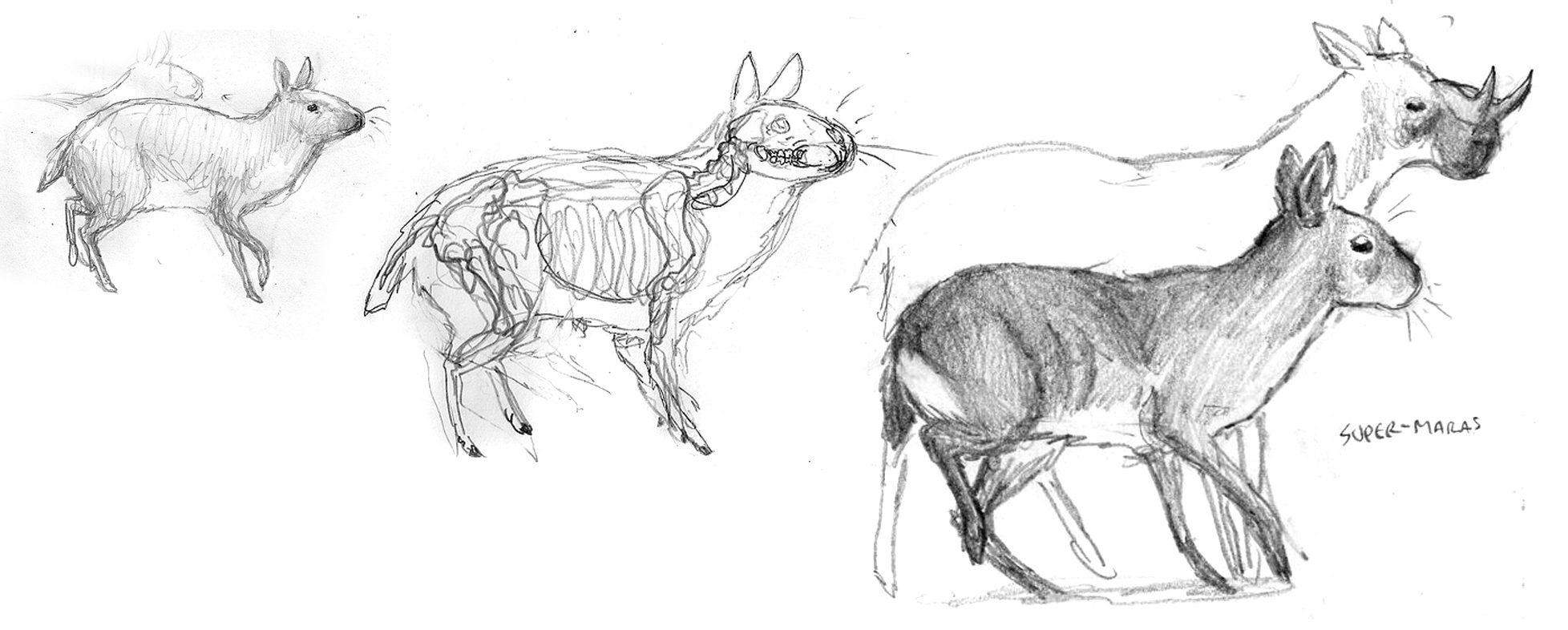

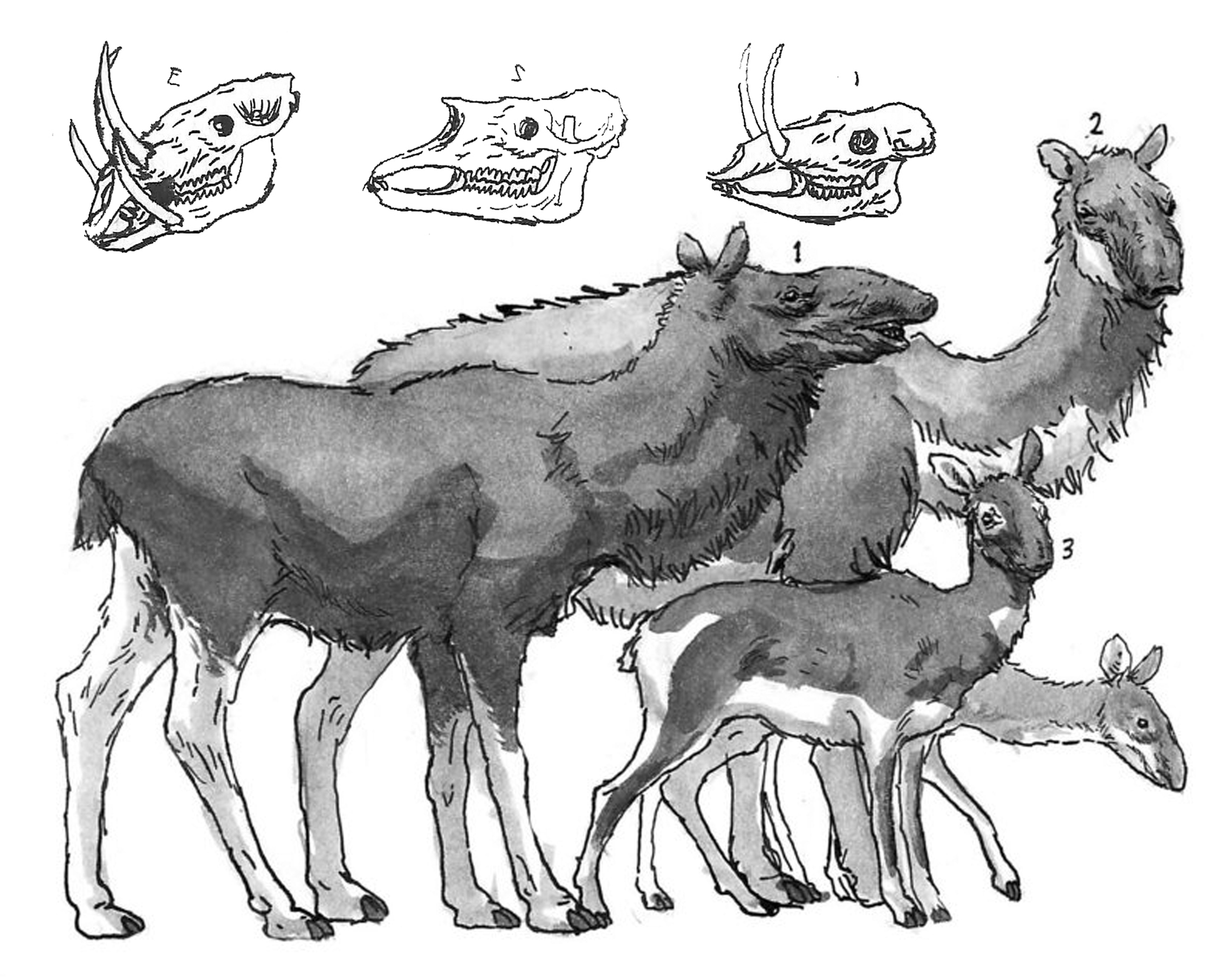

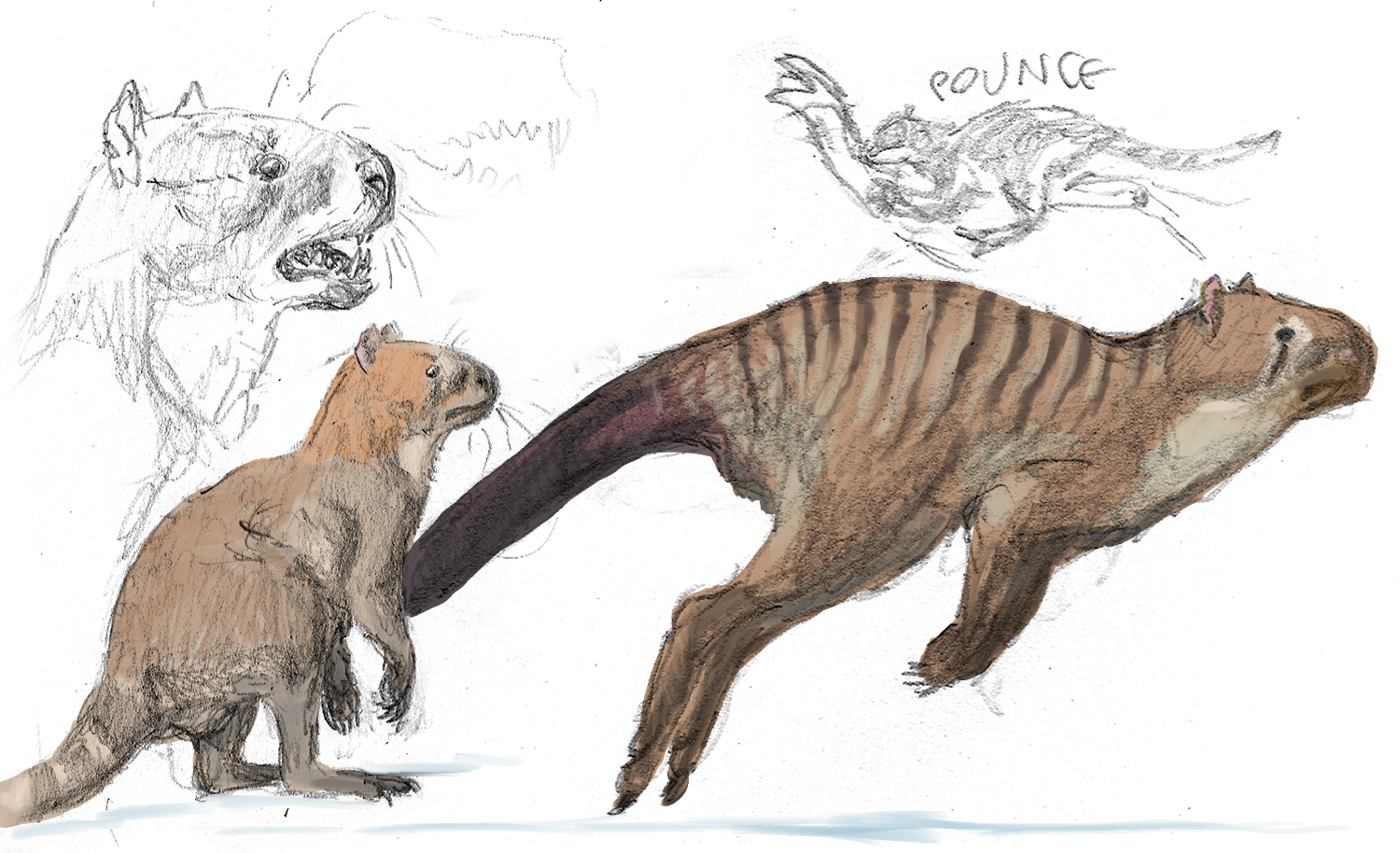

A series of studies showing the evolution of supermaras from rodent-like multituberculate mammals. The species depicted here is Ceratomegamys.

The full diversity of cursorial "supermaras", from left to right: The burly, tusked Odontobovis; the superficially-camel-like Tuberculocamelus; the gazelle-like Odontocervoides; the trunked, moose-like Pseudalces; and the two related forms - the big, desert-dwelling Macropseudalces; and one of the many deer-like Cervopseudalces species.

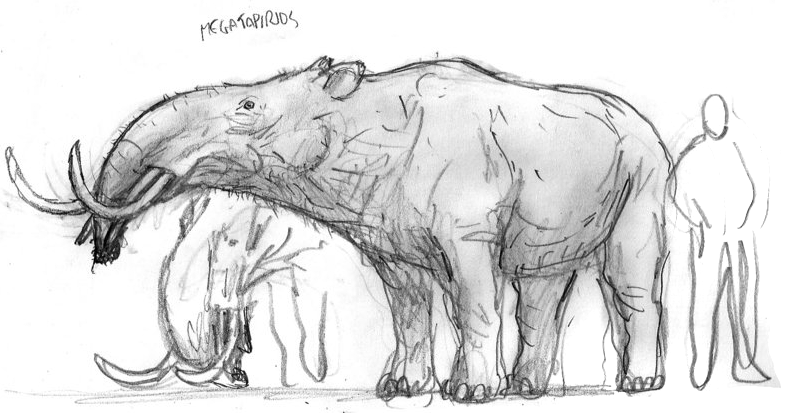

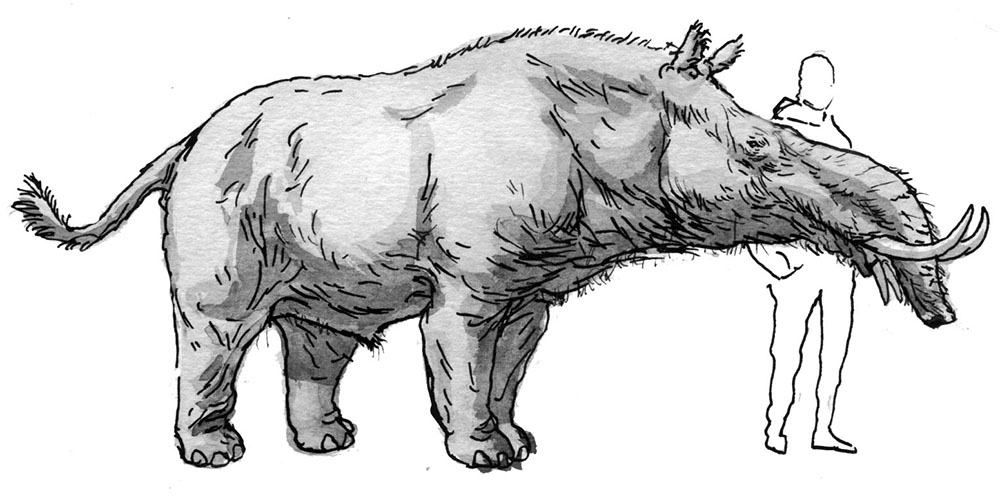

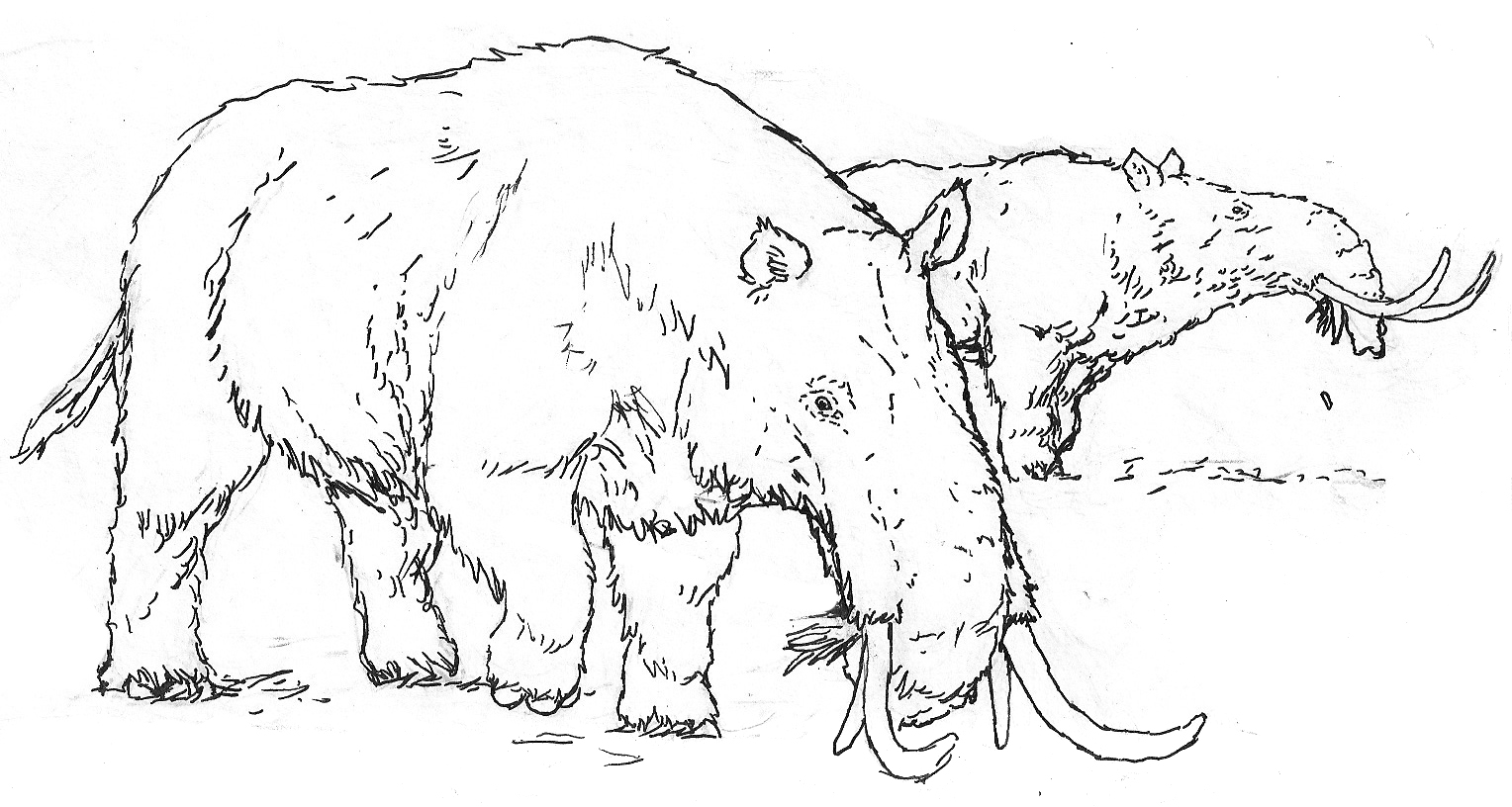

Studies of Megatapirus, large, superficially-elephant-like mammals that live in far-northern climates.

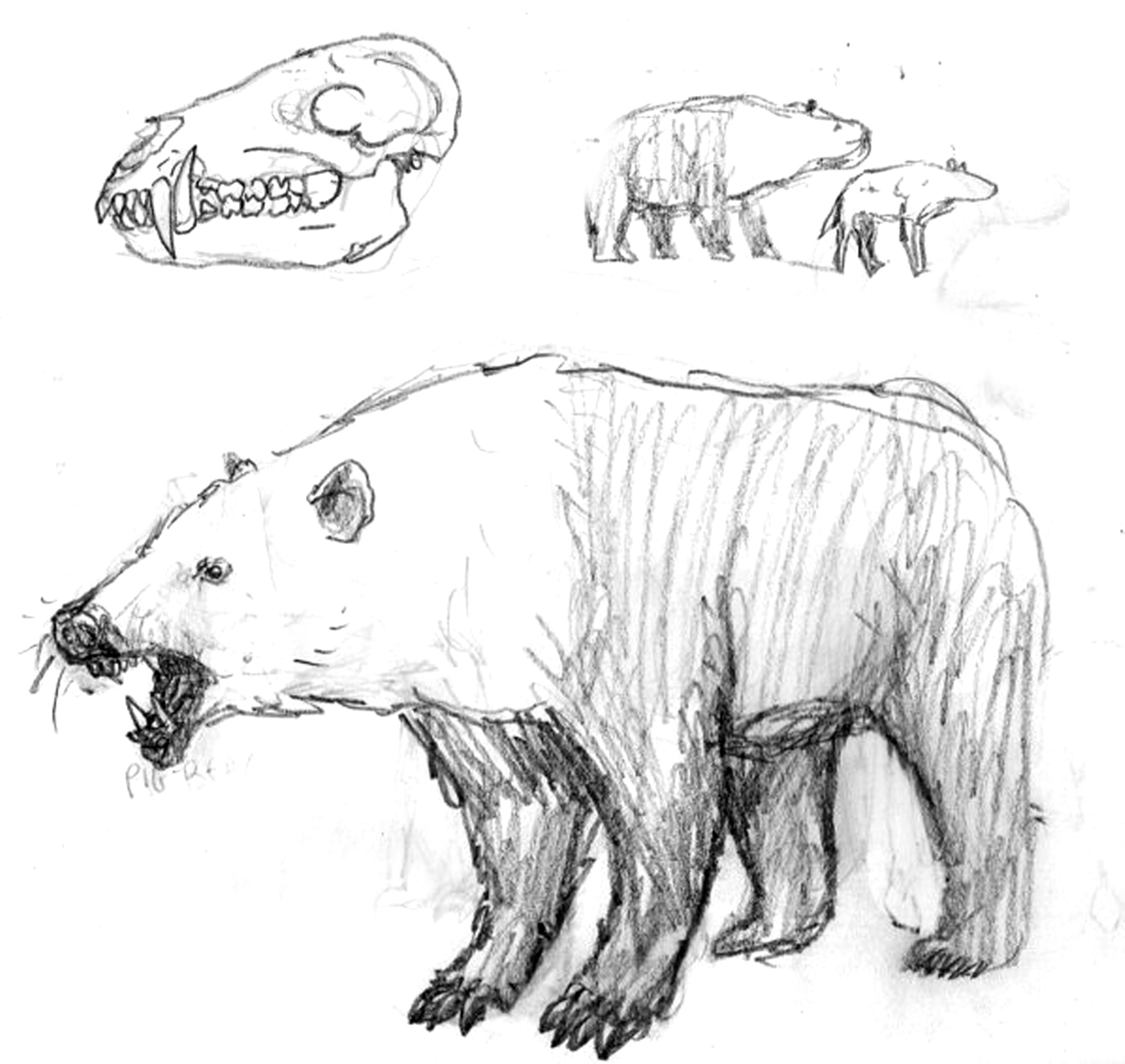

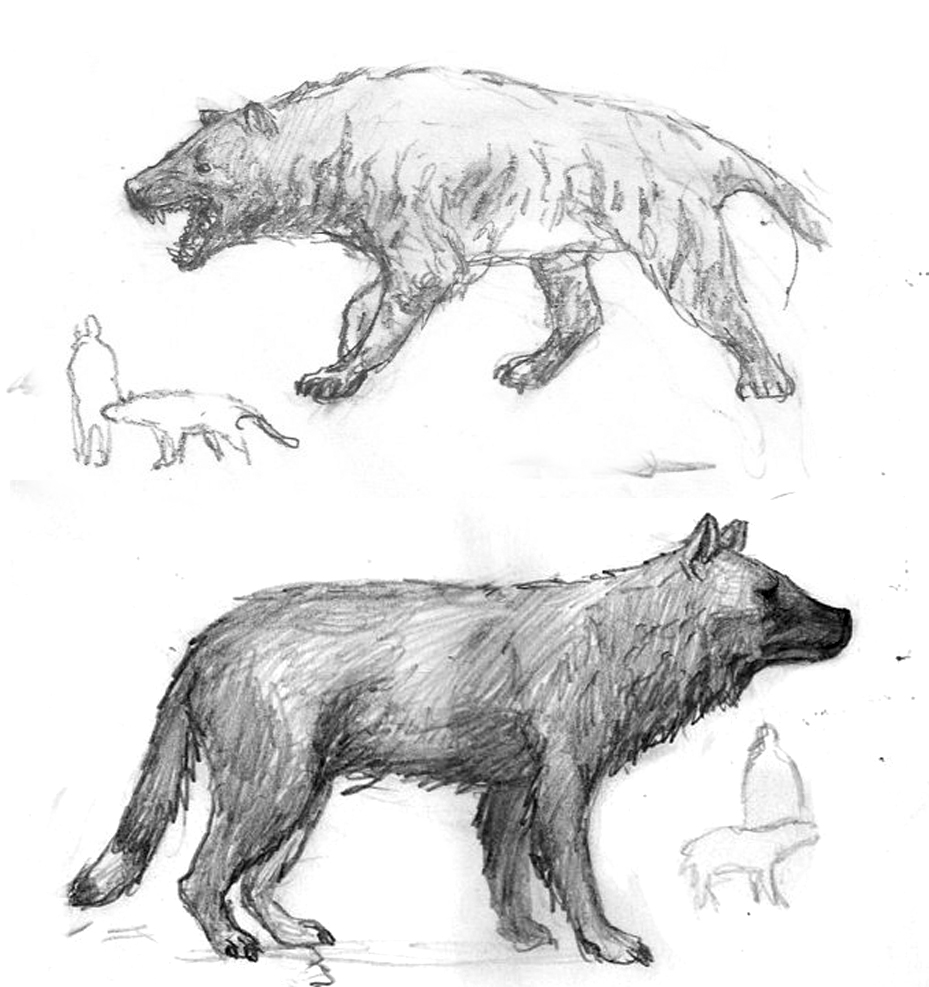

We also derived a variety of mammalian carnivores, mostly from marsupial stock. Through the honing forces of evolution, we imagined some would look very similar to the canid predators we have in the present day - the actual difference would only be in their internal and reproductive anatomies. Above, clockwise: The large, badger-like Mephitursoides; the extremely dog-like Pseudokynos; the hyena-like Krokutadasyurus.

Some marsupial predators diverged from the mammalian body-plan, and evolved into forms roughly converging with the predatory dinosaurs. The raptorial, meat-eating kangaroo-equivalent Theropodoktonos and kin are potent predators in South America.

Two more divergent marsupials: The leopard/possum Phobodidelphyoides; and the monkey-like Marsupiolemuris, a social, arboreal form with a potential to evolve intelligence.

We also wanted to have flying reptiles - pterosaurs - still alive and kicking in our world. These extraordinary animals were already in decline by the time dinosaurs became extinct. So we relegated them to only a few roles, comparable to storks and other large water-birds alive today. Above is a flock of Diluvipterus; large, filter-feeding pterosaurs. Also note the solitary duck flying on the upper-left corner.

Another, flightless pterosaur, Cygnotherium, from the islands that now make up New Zealand.

A more unusual group are the avisuchians, descendants of maniraptoran dinosaurs that secondarily converged on the aquatic bodyplans of spinosaurs (which are now extinct in this timeline). Most resembled the short-tailed forms, Pisciraptor and Brachyornithoides seen above. These goose-to-dog-sized animals inhabit rivers and lakes, and occupied a niche comparable to otters today.

There were also long-tailed Avisuchians such as the Natatoraptor seen above. These animals inhabit open waters, and nested in estuaries and beaches.

A contemporary scene from Eurasia shows commensal life between mammals and dinosaurs. Two Pseudalces browse peacefully alongside two kinds of large ornithominids, Archganseria and Brontonyx. A tiny, heron-like troodont, Anatolocursor, can be seen between them, looking for small animals flushed out by the large herbivores' movements.

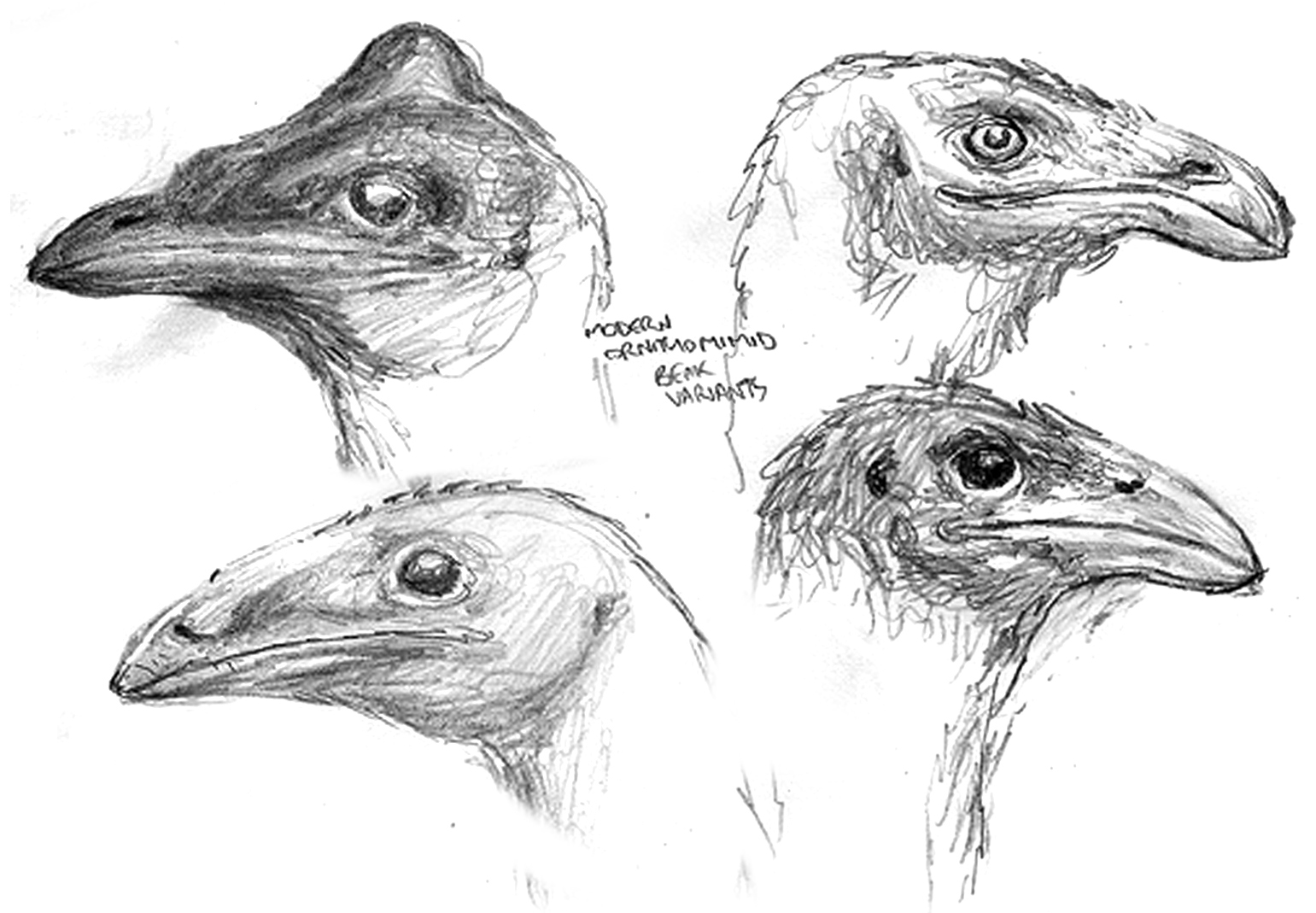

Nevertheless, despite co-existing with large mammals, dinosaurs are more diverse on this world. Herbivorous dinosaurs, such as these derived ornithomimids, constitute a large part of dinosaurian diversity. Above left are studies of Ganseria, a common, medium-sized browser. Above right, clockwise from the top right, are portraits of Ukkuloganser, another medium-sized browser; Nyctodromon, a nocturnal digger; Adzuganser, a small omnivore; and Pyramidoganser, a crested form native to the Nile Delta.

A scaled study of Brontonyx, a heavyweight ornithomimid herbivore.

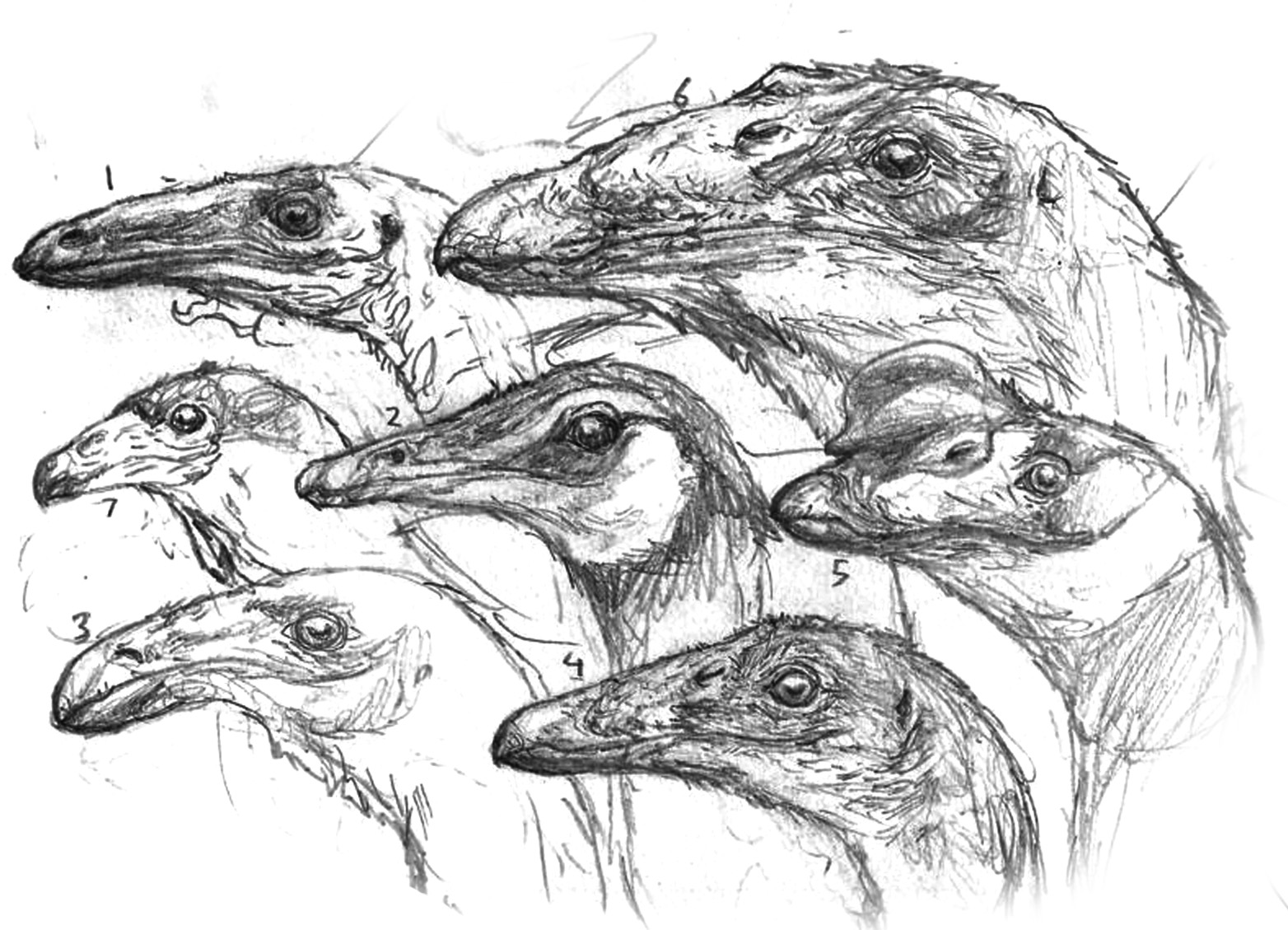

Portraits of many cursorial dinosaurs from across Eurasia:

1- Leptoganseria, a mountain-dwelling ornithomimid browser found on the mountains of what is now the Caucaus.

2- Ikiridectes, a troodont that mostly hunts small digging mammals.

3- Aktardektes, a small ornithomimid that has specialised for cracking hard-shelled nuts.

4- The gracile, juvenile variant of Brontonyx, (6) which occupies a completely-different ecological niche as a generalist omnivore.

5- Rugocursor, a widespread, broad-beaked ornithomimid with many species, common across North Africa and Eurasia.

6- The adult form of Brontonyx, a gigantic ornithomimid that feeds on trees, and defends itself with heavy claws.

7-

A vulture-like Cynornithoides, an extremely bird-like troodont, a frequent commensal of Avisapiens and related intelligent species.

A variety of Rugocursor, a mostly-herbivorous ornithomimid with adaptations for running.

Various troodonts, small-bodied, sometimes very bird-like omnivorous dinosaurs, distantly related to the Avisapiens lineage. Left, shaded study of Variocursor, a common, heron-sized, striding predator on small animals. Right, from top to bottom; Vuuria, a herbivorous form common across Eurasia; Boreocursor, a cold-climate predator, related to the Variocursor seen on the left; and Paravuuria, an omnivorous form.

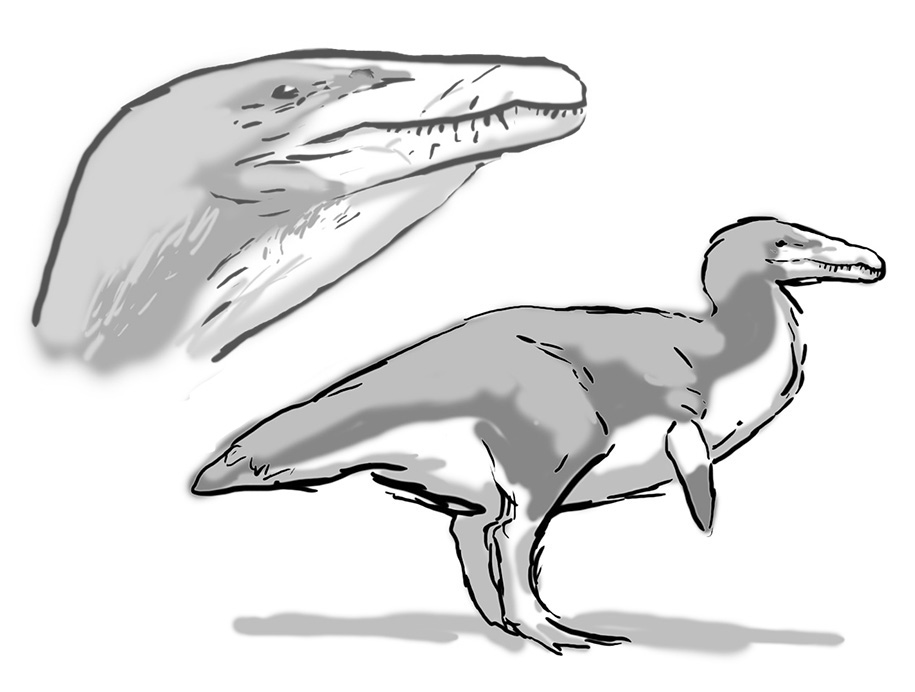

The last descendants of hadrosaurs, the famous "duck-billed dinosaurs", still roam in South America. The hoofed, sheep-sized Ornimastax seen above left, is a typical example. Australia, as in our world, is home to an unusual radiation of forms whose relations to animals on other continents are not very clear. Brachygullagong, seen above right, is a troodont-like form whose duck-like skull and batteries of grinding cheek teeth have secondarily converged with those of the hadrosaurs.

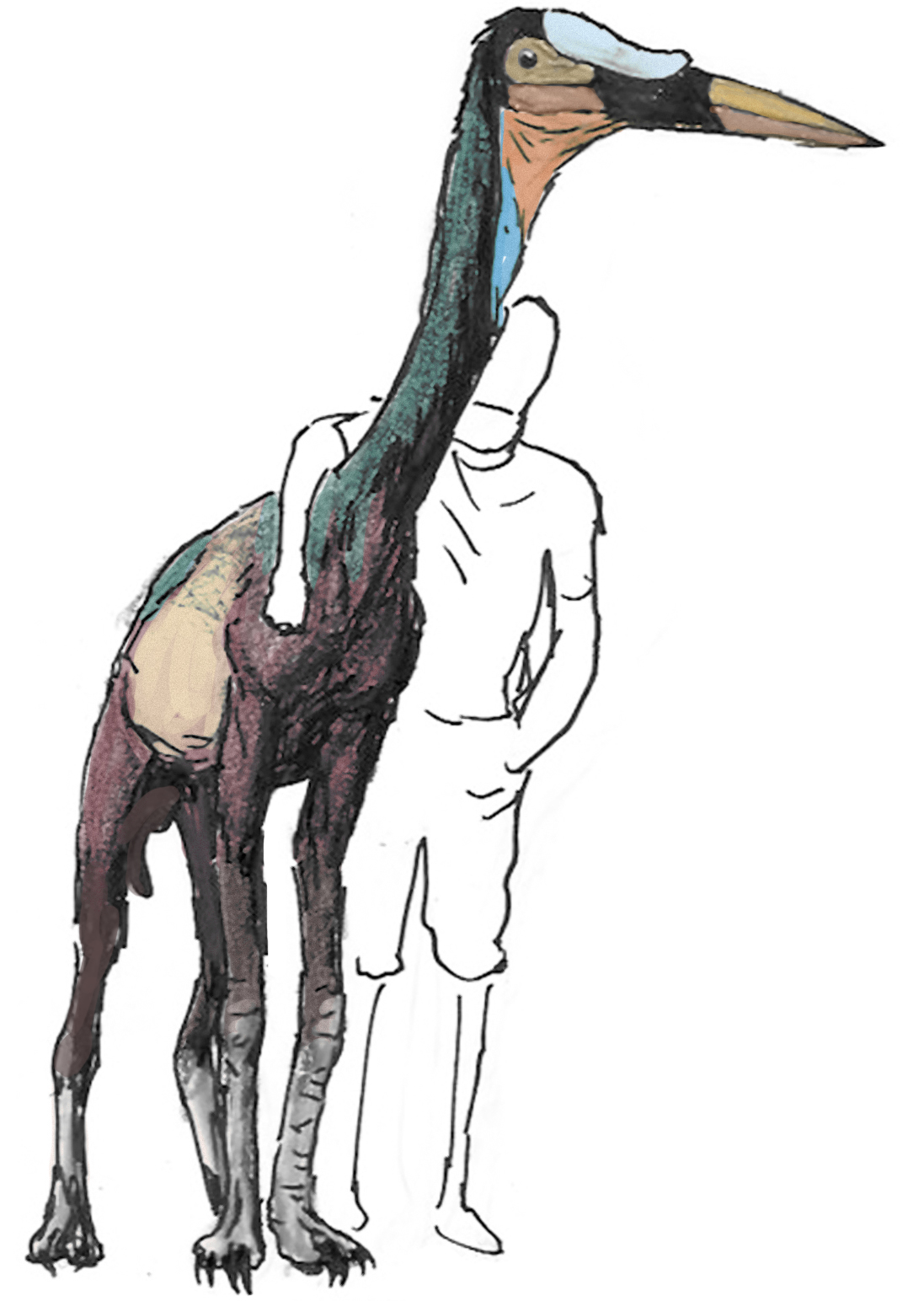

The largest herbivores on this world are long-necked, scythe-clawed ornithomimid relatives known as avititans. The largest species on Eurasia is Avititan bicolor, seen above in scale with a human figure.

Avititans owe their ecological success to their strong social structures and their care of their young. Here are two Eurasian avititans with their offspring. Yellow-tailed enantiornithine tick-birds, Parasitophagus leucurus, can be seen on their backs.

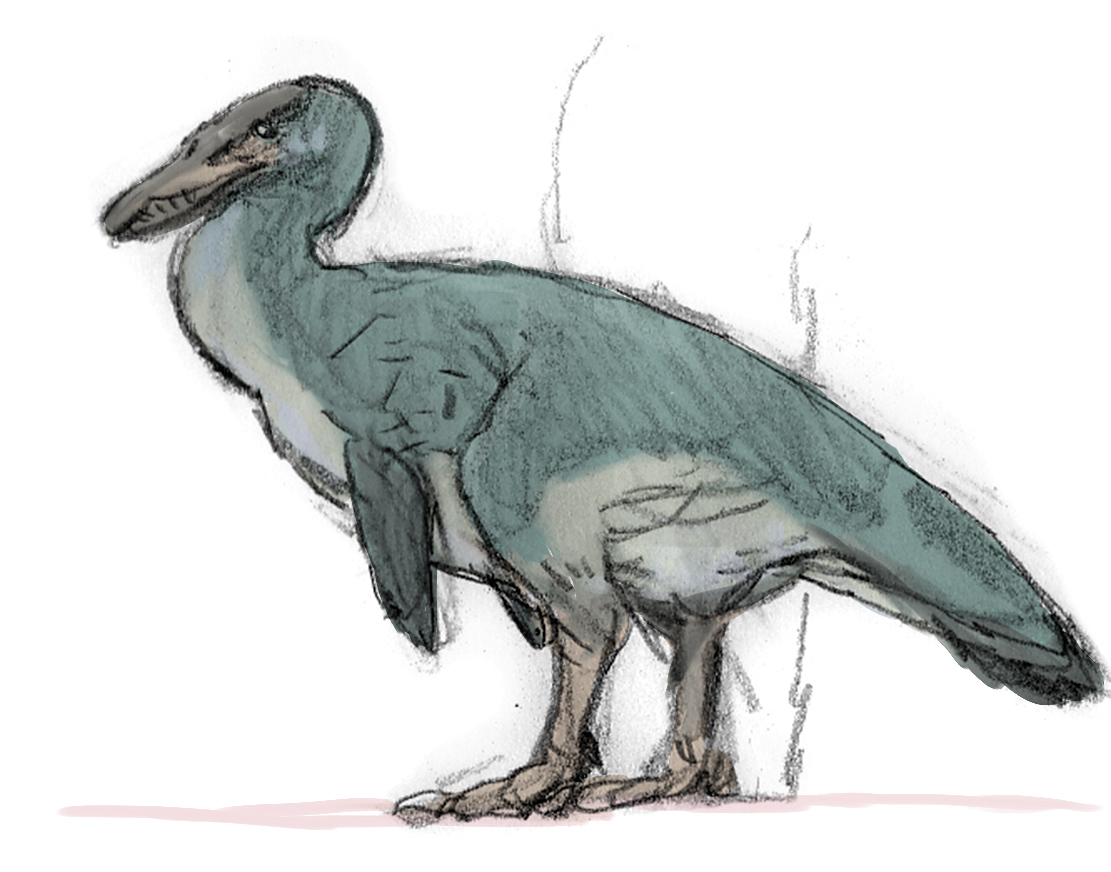

Oviraptoriformes made up another important clade of dinosaurs in this world.

Descended from bird-like ancestors, various clades of these animals live on as important omnivores, scavengers and even predators in many ecological niches. Above is Eblisornis, a common species found throughout Eurasia.

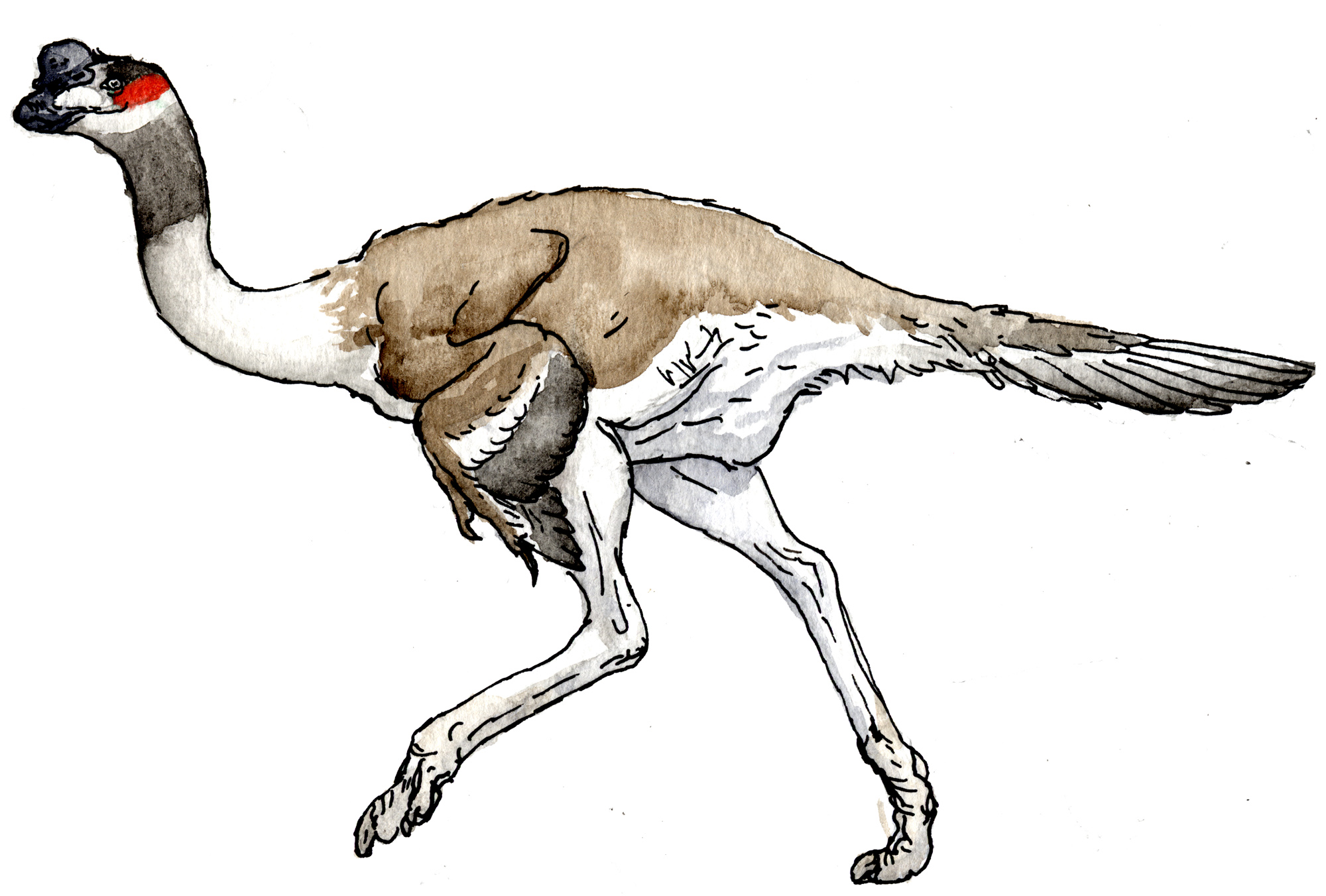

The bull-bird, Bosornithoides erythrops, is the largest and most prominent oviraptoriform on the Eurasian continent. It subsists mostly on plants and fruit, but will eat carrion if given the chance.

Hunting the wary and dangerous Bosornithoides is an important rite of passage for dinosauroids. The animals require coordination and group-work to bring down, and hunting one is a bonding experience for batches of young-adult nestmates. This ritual not only cements the dinosauroids' social standing in their tribe, but also bonds the hunters together for the rest of their lives. The four hunters-to-be in this picture are accompanied by a couple of jackal-birds (Cynornithoides), domesticated pets that are almost as smart as the dinosauroids themselves.

Many dinosaurs dabble in carnivory, but the main predatory niches on this version of Earth, are occupied by a diverse radiation of paradromaeosaurs, descendants of the famous "raptor" dinosaurs and kin. Paradromaeosaurs have diverged considerably from their ancestors. One lineage, known as the rhynchovenators, replaced their teeth with sharp, raptorial beaks.

The male and female of the common boreal rhynchovenator, Rhynchovulpes agilis.

A lean-legged Egyptian rhynchovenator, Rhnychovulpes aegypticus, atop a dead multituberculate mammal. The key to rhnychovenators' success is their added tenacity and stamina. Even a small rhynchovenator can overcome comparatively large prey by continually harassing and chasing it into exhaustion.

The bald-headed Osteophaganax regalis is a common scavenger encountered across the Caucaus Mountains. Its males develop striking, black-and-purple wattles on their faces during spring.

Two more derived troodonts. Left, a tree-dwelling arbosaur, Toucanops dixoni, from one of the diverse and little-understood clades found across the South American continent. Right, the lean, narrow-beaked Halophagus sp. from fossil deposits in what is now China. This group evolved specialisations for marine diving and probably saltwater drinking, before becoming extinct during the Miocene.

The dominant guild of maniraptoran predators, the tyrannoraptors, evolved from "regular" dromaeosaurs with powerful, biting jaws. Some species living today, such as the Savannahdromeus shown above, are still very similar to the earliest forms. Despite its small size, the smart and social Savannahdromeus are apex predators thanks to their pack-hunting behaviour.

Another basal tyrannoraptor, Pantherdromeus - is a solitary hunter that is common across much of Eurasia. It probably represents a diverse and subtly-variable species complex.

Solitary, basal tyrannoraptors eventually gave rise to the terrifying main-line tyrannoraptors in the last twenty-million years. The evolution of these animals was marked by the reduction of their wings and the enlargement of their legs, and jaws. Their tails developed into stiff and rod-like balancing organs. In some respects, they were the evolutionary echoes of the big-jawed, running tyrannosaurs, which had become extinct earlier on, during this world's version of the Eocene period. Unlike tyrannosaurs, however, tyrannoraptors had well-developed social behaviours and intelligence; which, when coupled with their fast speed and terrific jaws, turned them into formidable apex predators. Above are the adolescent and mature forms of Metadromodaemon phobetor, a mid-sized hunter found in the Middle East and North Africa.

A scaled drawing of Wotandromeus bicolor, the terrifying, large-headed hunter of European forests.

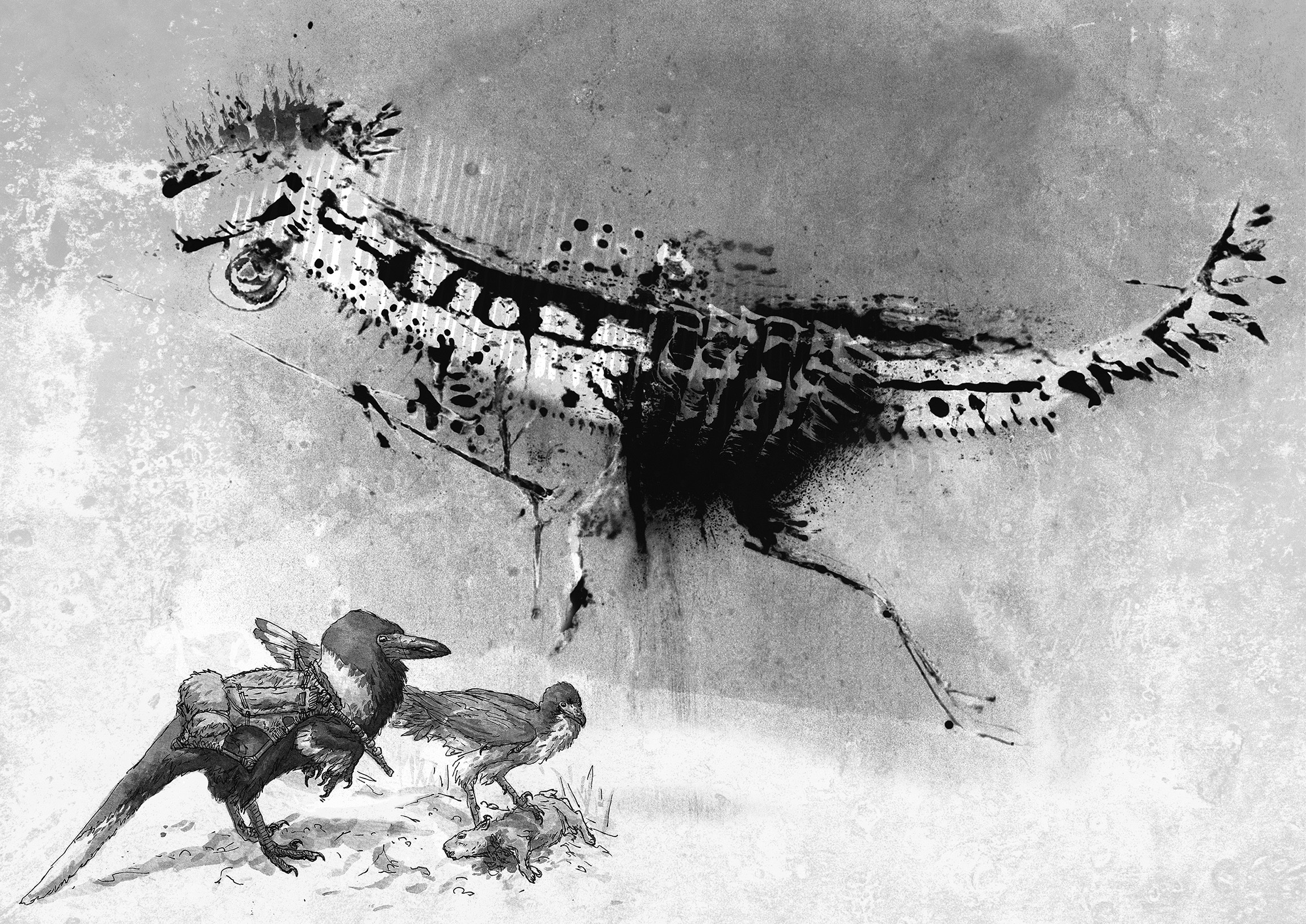

The seven-metre-long Melanorodromeus euceratus - also known by the Dinosauroids as "black thing" - is the largest predator on mainland Eurasia; but even larger forms are reputed to exist in Siberia and North America.

Let us now return to the Dinosauroids, their culture, and art. Above is a brief study illustrating the divergence of the two species of Avisapiens; A. saurotheos and A. tataricus, from ancestral eu-troodontid stock.

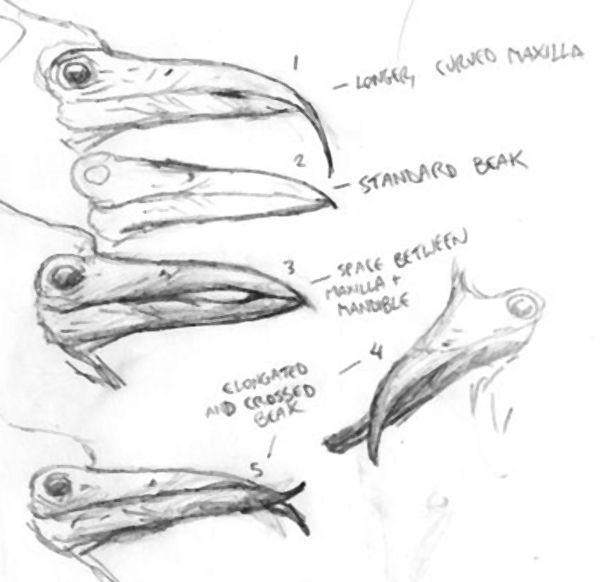

Especially A. tataricus shows considerable variation in beak shape, length and colouration. Above, right are the colouration of the Eurasian (top right, bluish-black), and Northeast Siberian (above right, yellowish-brown) races. Above, left shows a spectrum of variation in A. tataricus beaks. The cross-beaked and long, curved beaks occasionally crop up in certain bloodlines, which also have augmented song-memories. These individuals are revered as shamans in certain A. tataricus tribes; or are immediately killed-off as harbingers of doom in others.

Above, the extensive variation in the head shapes, beak lengths and crests of various races in A. saurotheos. The bottom-right sketch depicts a hybrid individual between A. saurotheos and A. tataricus.

A powerful hunter of A. tataricus, from the Carpathian Mountains, showing a stone axe and bent spear that are characteristically used by this particular tribe.

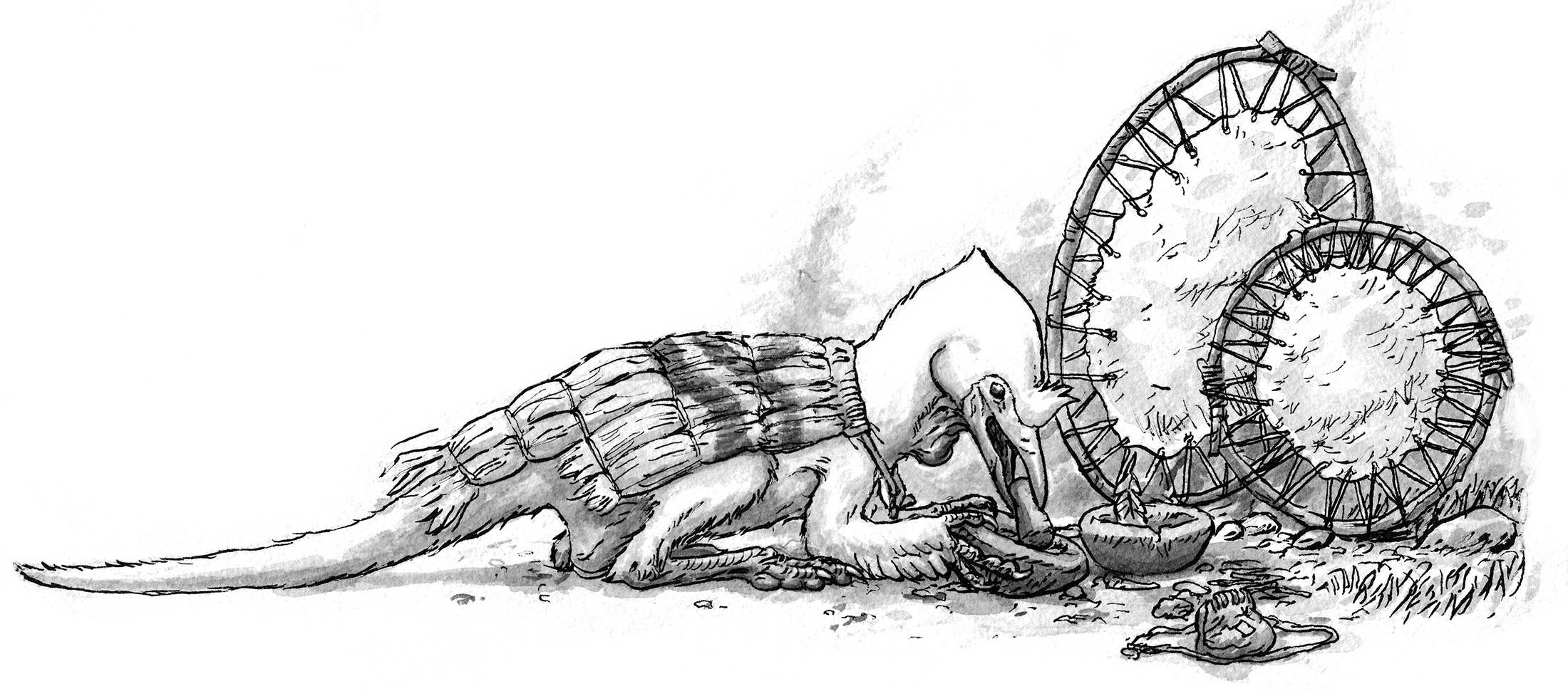

An artist/shaman of one of the settled A. saurotheos tribes living around the Balkans. He paints on animal skins stretched taut across circular frames, and paints using ground-up soil and other pigments, wielding a brush made from a wing-feather. The skin canvas also double as drums.

Art is one sure-fire way of identifying an intelligent species. This skin-painting shows a spear-hunter and prey, a painting by the aforementioned shaman.

Painting of a god or hero-figure with red tail feathers.

Painting of two shamans divining the future from the entrails of a dead flying animal.

Painting of a hatchling being trained by a village elder.

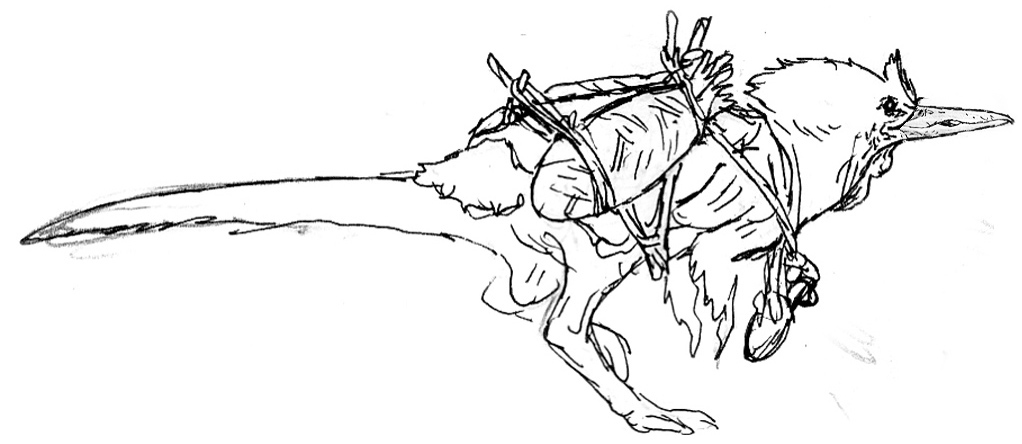

Studies of an A. saurotheos wanderer with a travel harness; and a duo of A. tataricus migrants with a domesticated bull-bird, a relative of the oviraptoriform Bosornithoides mentioned above.

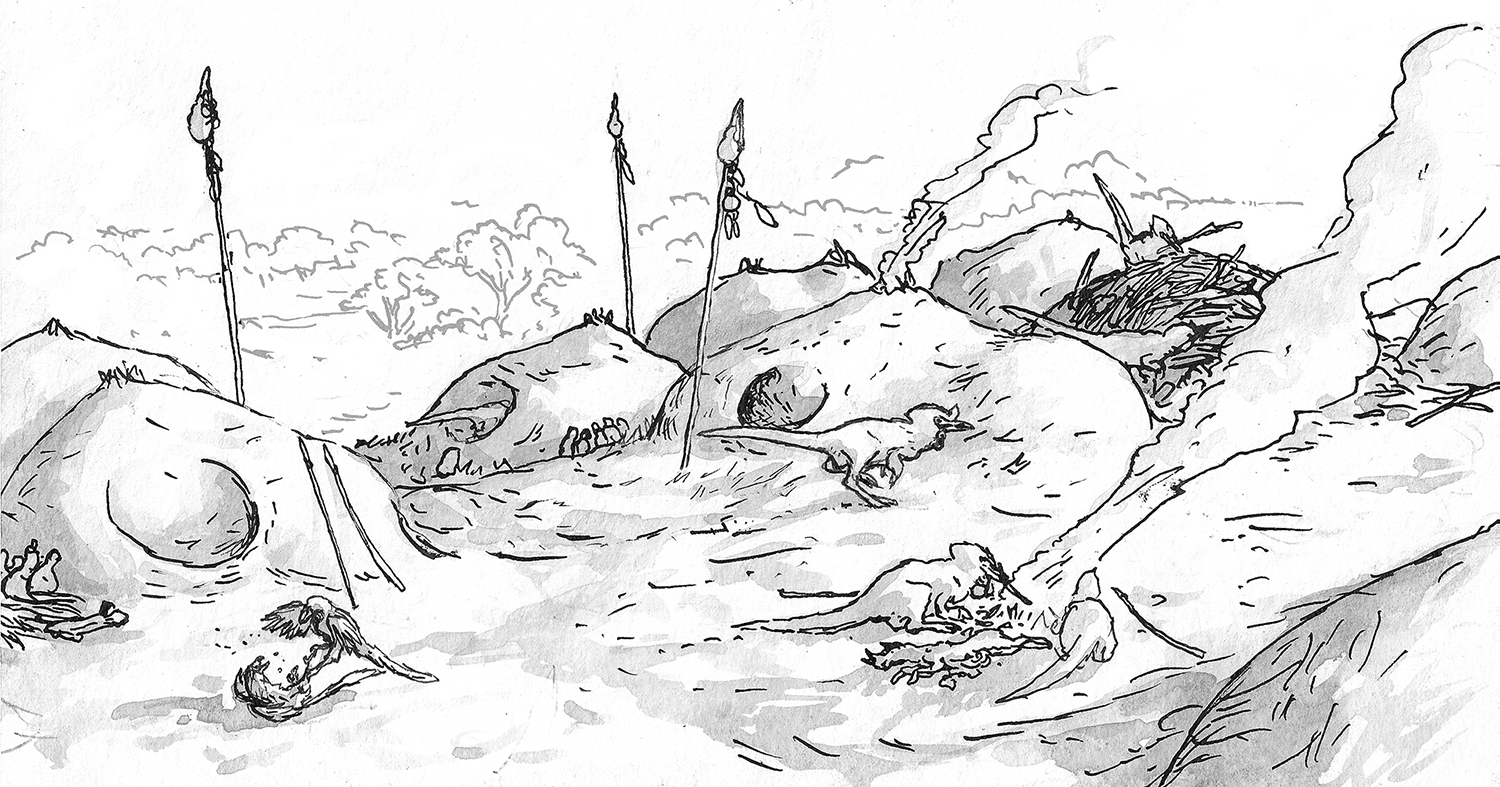

The view from an Avisapiens saurotheos village, showing the species' characteristic nest-houses, and a pair of semidomesticated Cynornithoides jackal-birds playing in the village square. Note the heads mounted on tall poles, a sign of reverence to the spirits of the departed.

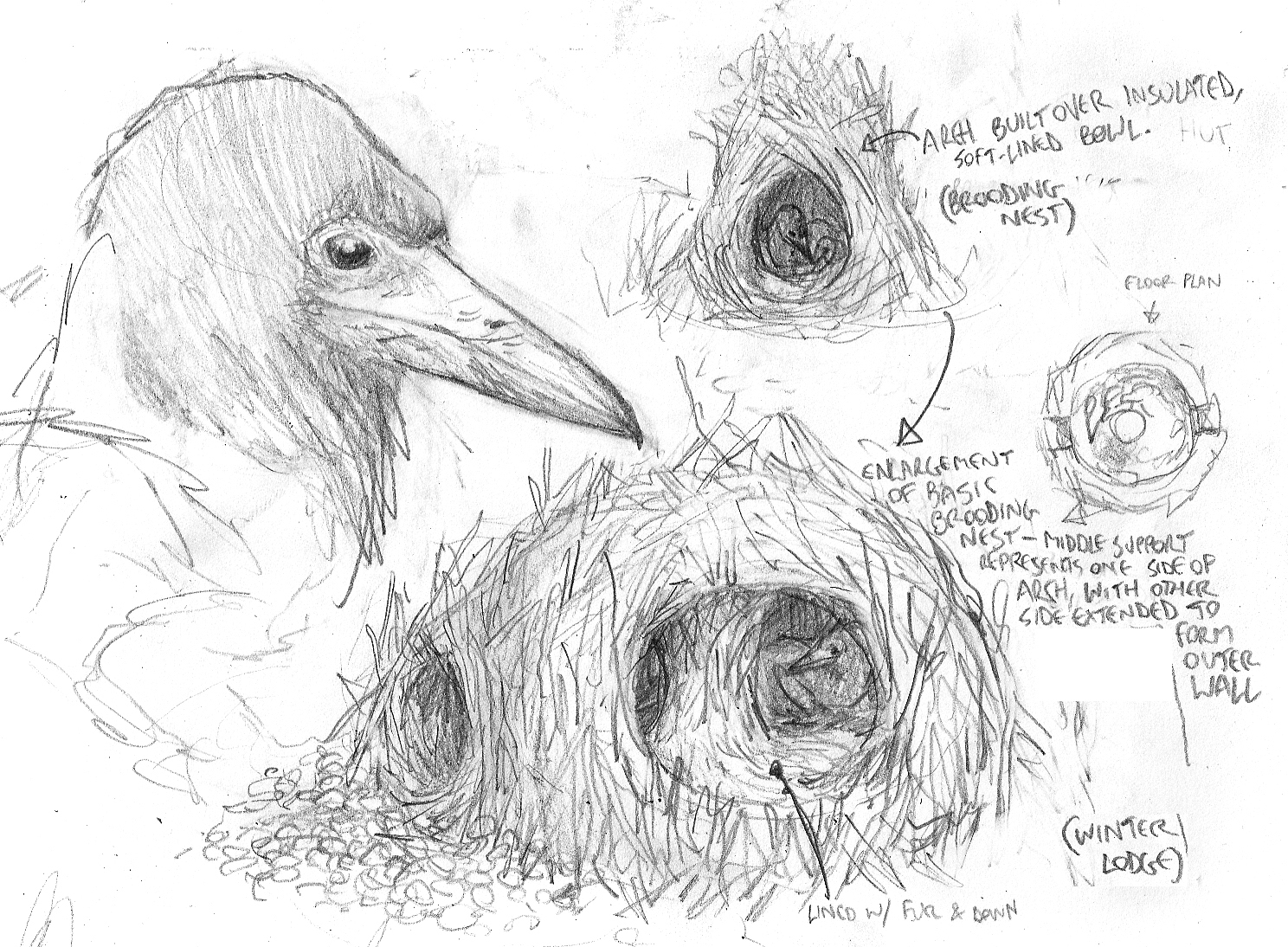

Detail of a brooding nest constructed by Avisapiens tataricus. Most tribes of these species are migrants that range across Eurasia, few build permanent structures.

Sketch of an A. tataricus wearing a travois-like travel harness.

Study of an A. saurotheos wanderer with travel gear.

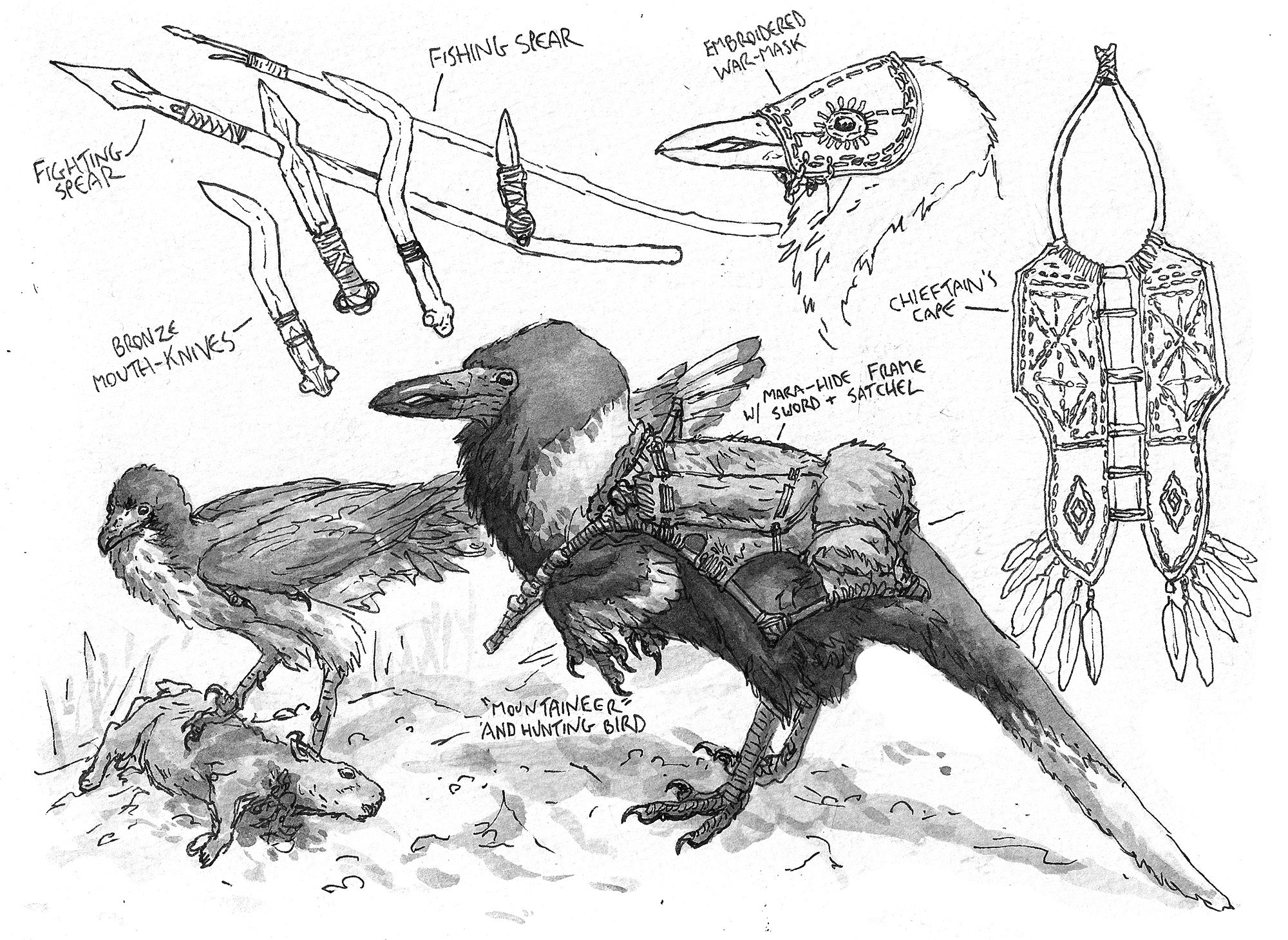

A detailed study of the burly A. tataricus native to the Caucaus Mountains, complete with weapons, travel gear and ornamental cape.

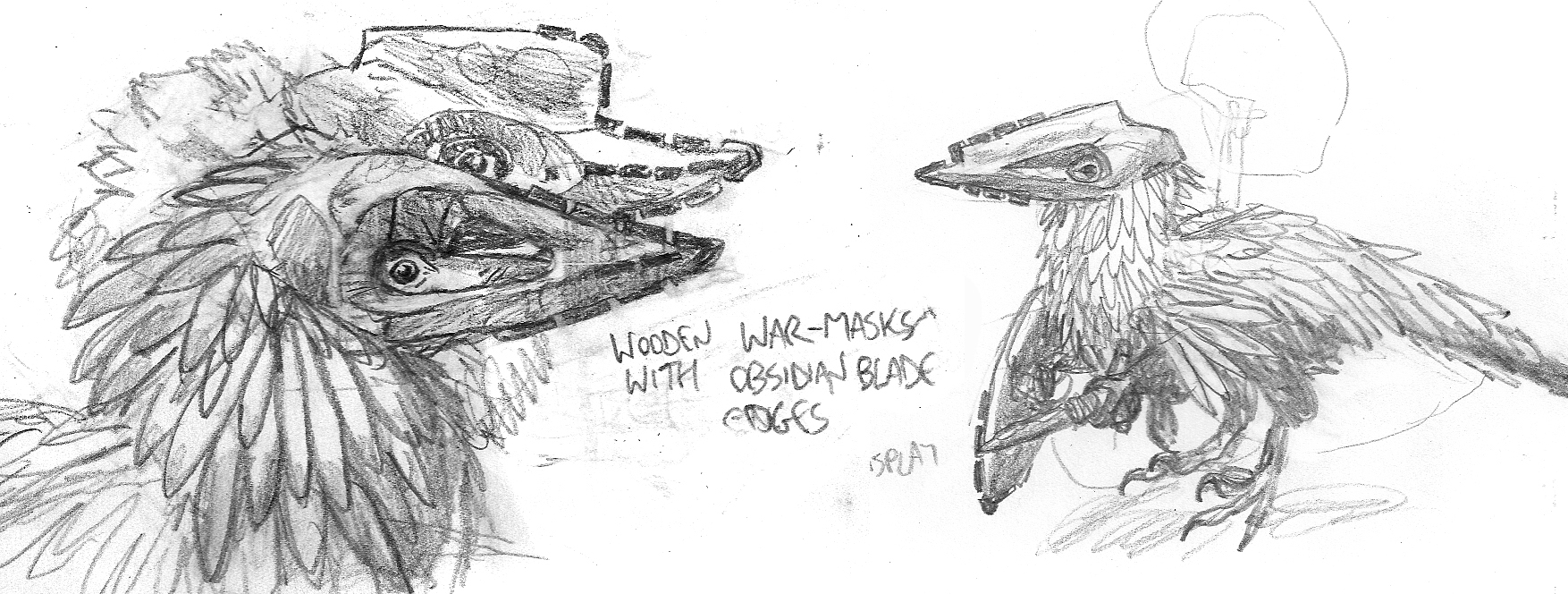

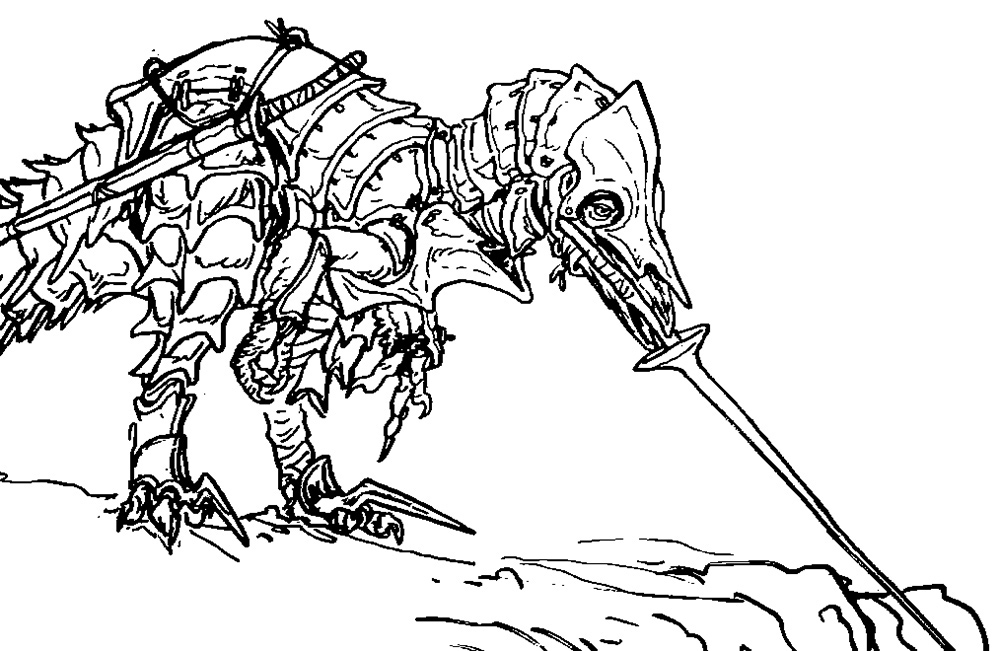

Sketches of war-like A. tataricus tribes native to the Eastern Mediterranean region. These tribes are known for their ferocious (if impractical) war-masks.

Studies of two diferent warriors from two different Avisapiens tataricus societies.

A resplendent A. tataricus warrior from the Levant, wearing an ornate head-dress of feathers, and an obsidian-studded war-mask.

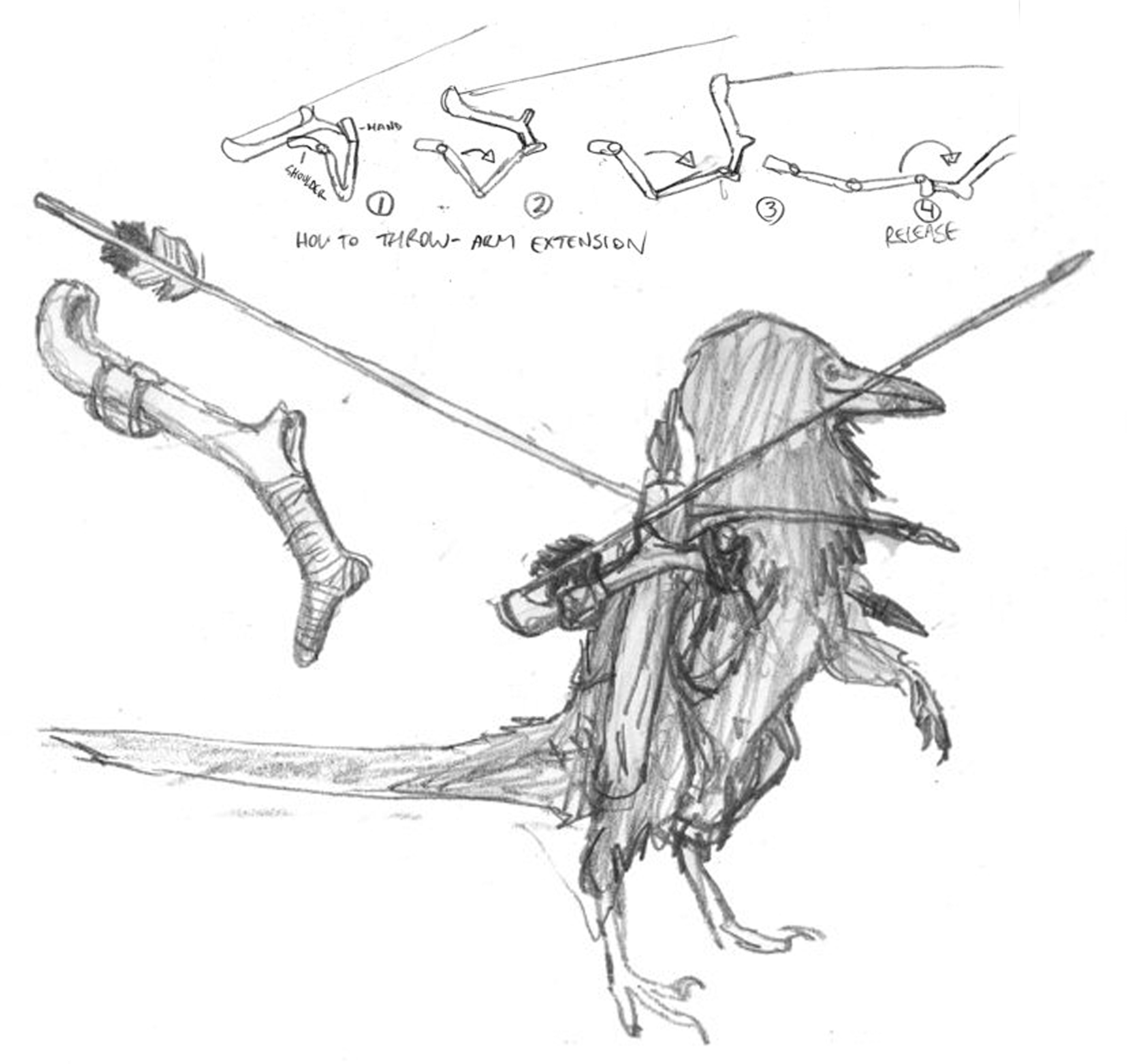

Studies for Avisapiens spear-throwers and wooden-slat armour; from a comparatively advanced period on this species' societal development.

An A. saurotheos shaman entertains hatchlings with fireside tales of spirits and other worlds.

A band of slave-keeping A. tataricus warriors during a raid to an A. saurotheos village. A young shaman is captured and de-clawed.

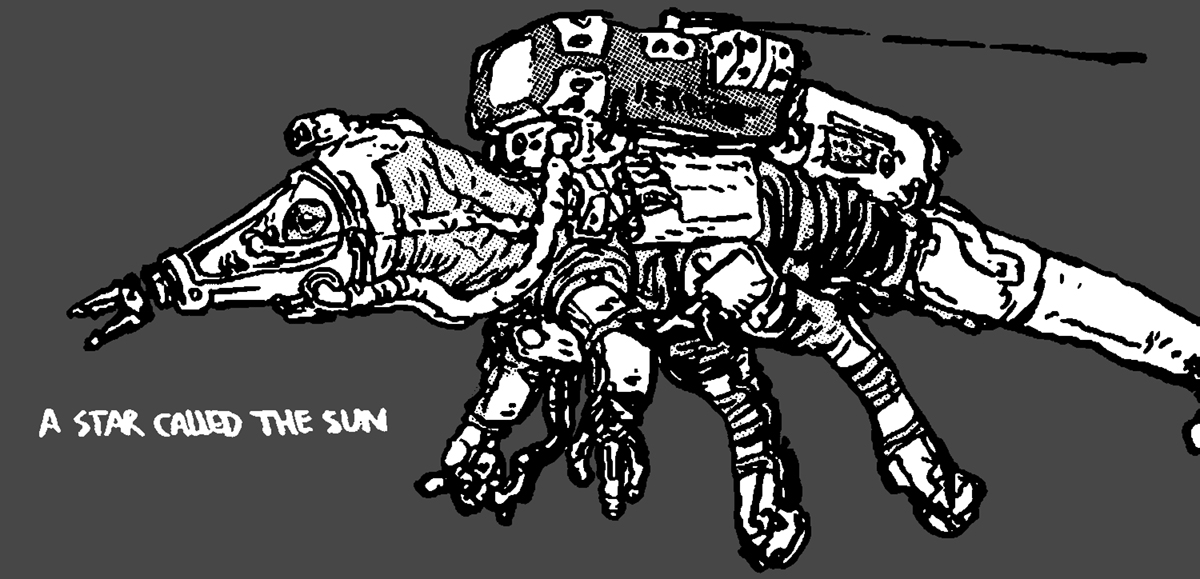

Simon Roy and I also dwelled on the far-future evolution of dinosauroid technology. The sketches above of a "knight", moon lander and an astronaut were produced, but we did not pursue these scenarios seriously.

Let us conclude our visit to the dinosauroid tangent-universe with one last look at our artist/shaman, his village, and his paintings. Somewhere in deep time, they are still alive, and still waiting to tell us of their adventures.

A painting of an avititan family.

A painting of the dangerous, predatory "black thing".

A painting showing numerous animals at a watering hole.

A painting showing an A. tataricus warrior.

Stylised paintings of spear-wielding Carpathian warriors.

Painting of a ferocious Aegean headhunter.

A stylised painting showing an immature dinosauroid.

Stylised painting of a warrior confronting a spirit-creature.

Stylised painting of a powerful Caucausian mountain warrior.

Painting showing a ghoul-like oviraptoriform animal.

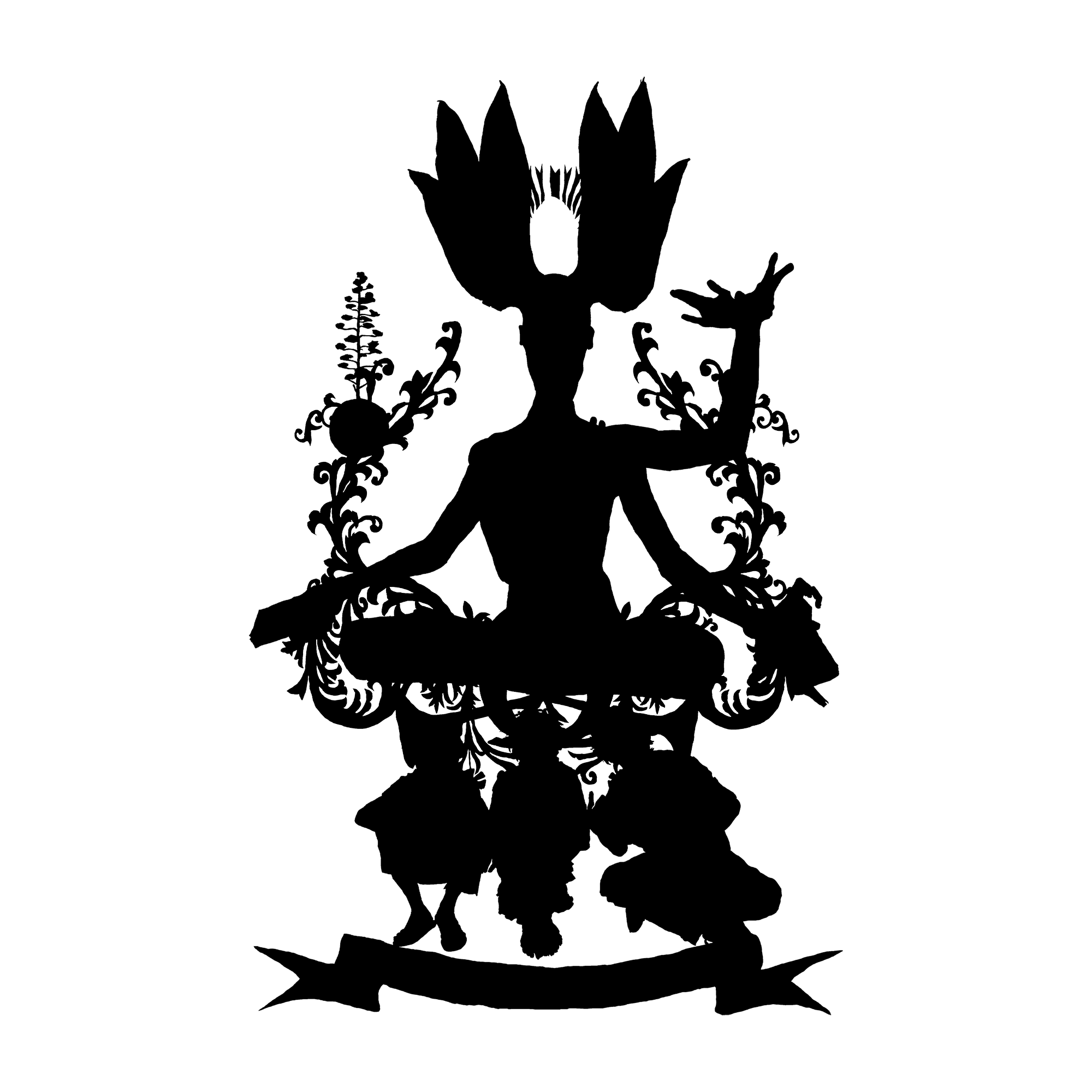

Painting of one of the sky-gods worshipped by A. saurotheos.

A complex painting showing four A. tataricus warriors hunting a bull Bosornithoides.

Simon Roy and I may return to the dinosauroids universe one day with a real story; but truth be told we enjoyed world-building far more than inventing stories and characters.

- Created in 2008 and updated in 2019.

***

Copyright laws protect all content associated with this site.

Artwork on this particular page belongs to Simon Roy, and has been used with permission.

Contact c.m.kosemen@gmail.com for inquiries.

***