C. M. Kosemen

Artist and Researcher

***

Towards an Alliance of Societies:

The History of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation Until the Year 2099

Originally written as part of the collective world-building exercise held for the NATO 2099 comic book project in 2023.

HISTORY

As it entered its 150th year, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization found itself facing an unpredictable and multifaceted set of challenges.

The crises and conflicts the Alliance had faced in the past decades – the protracted spate of conflicts involving Russia; the Asia-Pacific crises; the first and to date, sole use of a tactical nuclear weapon (still called a ‘battlefield accident’ to avoid further complication); the accession of Australia and the Philippines; the earthquake emergencies and the climactic migrations; the decades of famine, strife and in cases, the near-genocidal civil conflict affecting member countries – need no further retelling in this brief essay. It was, as a leading philosopher of the era had commented; “a turbulent seven decades in which the world had produced enough history to keep its savants, artists, and poets busy for the next seventy...”

THE MISSION

Let us now turn to the mission profile NATO adopted in the aftermath of such a tumultuous era.

Dwight Eisenhower had famously stated that “...battles, campaigns, and even wars have been won or lost primarily because of logistics”.

The crises NATO had faced in the past decades had all necessitated the utmost from member states in terms of logistics – most often in extremely pressing circumstances; often with improvised, and in a few cases, tragically insufficient solutions. All member states understood that in the next global crisis – in whatever form it might take – the price of failure may be fatal.

Thus, NATO refined its mission going into the 22nd Century as “to guarantee the freedom and security of its members through social, logistic, and military cooperation”.

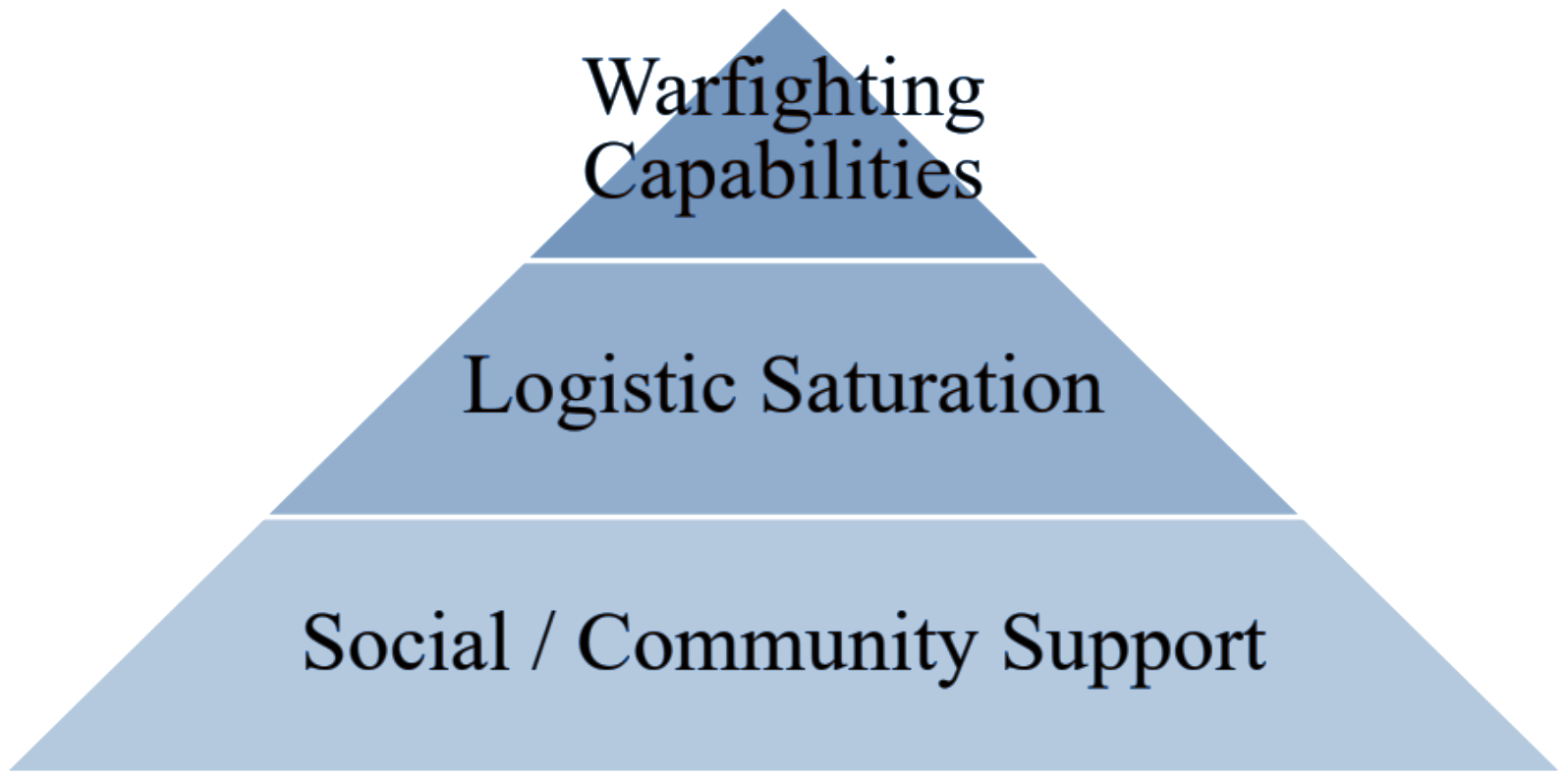

A three-level “ziggurat” of organization was established to serve this mission – and at each level there were massive responsibilities.

Enhanced warfighting capabilities were only the capstone of this mighty pyramid. Below it was a newfangled, unified logistic network – the size and strength of which the world had not seen after the Second World War. And supporting that, in turn – was a broad and pervasive network of social services stretching across member states.

SOCIETY

The bedrock of this new strategy was the foundation, and continued support of social and community links – not just among NATO member states, but also within member states themselves.

The calamitous social crises of the early 21st Century - alongside the pervasive risks posed by information warfare in a world where nearly all literacy was digital - had shown that the vulnerabilities fraying the social fabric all too clearly. Pre-existing state structures were too cumbersome, or insufficient to bolster social conditions. Private initiatives were likewise insufficient – and at any rate mostly palliative in nature. In the past adversaries had exploited these weaknesses through newfangled digital propaganda - all too freely and all too grievously.

It was widely known that the cost of an advanced stealth bomber could well offset the yearly budget of a health ministry of a developed nation – and in some wars of the 20th Century, NATO’s strongest member state had spent in a day, sums of money that could have solved its nascent health, housing and education problems before they could assume the disastrous consequences that led to so much grief and hardship later on.

But NATO’s approach in 2099 meant more than mere allocation of funds. Simply throwing money at the problem would not ensure the restoration of social stability; nor would it alleviate the inequality, the desperate alienation, and the lack of hope that had damaged societies in the first place.

To this end, the Alliance now ran vocational schools in its member states. These were not limited to the capitals, but in most member states extended down into the town and county level. Wherever they operated, NATO schools optionally complemented national education.

They offered instruction in anything from languages of member states and social media literacy – to basic know-how that regular curricula had made a point of not touching; how to start a personal company, how to become a small business owner, how to file taxes and manage finances, how to install boilers, domestic wind turbines and solar panels, how to repair a house frame, how to lay a brick wall, how to safely install electrical wiring, and so on... Admission was free, and students could drop in and out as they wished – or complete their courses in different countries.

The Alliance also worked directly to address further social issues. Under special international agreements, the Military Engineering Centre of Excellence (MILENG COE) oversaw the construction of affordable social housing, and coordinated the restoration of pre-existing urban centers – most of them as thoroughly damaged by decades of social conflict and rapacious zoning practices as any war.

Even after the plateauing of population growth there was a dire need for affordable, decent housing. Many people – not just in war-torn Eastern Europe but also in Western member states such as the United Kingdom and France - lived and raised their families in “NATO houses” and “NATO apartments”. This, too, helped ensure a robust social fabric across the Alliance.

Beyond this, NATO’s efforts to bolster inter-member social cohesion included the NATO Youth Travel Pass. This great plan, echoing the European Interrail and Eurail passes in the decades before Russian conflicts; extended into air, bus, and ship travel and free hostel accommodation alongside railways – and was open to all people aged 18 to 32 in all member countries – regardless of their status as students. It was also priced at much lower cost, and most importantly overrode visa requirements - so that all who wished to travel and know the cities, the customs, and the people of fellow NATO countries could do so as they wished.

Perhaps more than any act – this plan left the happiest memories in the minds of citizens. Generations grew with excitement of going on “the NATO trip” (or “taking the YTP”) – and seasons spent thus led to innumerable friendships – not to mention a great many mixed families. Few could fall for anti-alliance propaganda after seeing and experiencing the conviviality of fellow NATO citizens first-hand.

A final contribution to social stability was the widespread establishment of NATO Free Clinics to offer free – or low-cost healthcare. These establishments, ranging in size from walk-in clinics to free trauma wards and full-scale hospitals, were especially common and poplar in the alliance’s strongest member state. Alongside offering training to military medical personnel; they complemented costly, burdened, or otherwise inefficient healthcare services.

Like the schools and the construction programs, these health services had a triple mission. First, they performed the services they were set up to provide, and contributed to the re- establishment of social fabric in member states. Second, they created a circulation of professionals among member states, familiarising them with fellow member states in the Alliance. Third, they associated the name of the Alliance permanently with good deeds and magnanimity in public perception across the globe – creating an “immunity” against pervasive adversary propaganda; driving an unprecedented boost in enrolment rates; and ensuring that many would in turn come to the Alliance’s service when the time came.

Throughout past decades, advancing digital technologies, media and psychological operations, and the blurring of virtual and corporeal life through social media had turned the entirety of the public and political spheres into an all-encompassing, holistic, total new domain of warfare.

In such a broad new arena, only the all-encompassing, holistic, and total support of social services and community links could provide a reliable form of defense and deterrence. Thus united, the Alliance rose up to the mighty challenge.

LOGISTICS

Now let us examine the second tier in NATO’s “ziggurat” of organization. As told before, crises of the past – be they wars, “battlefield nuclear accidents”, ethnic cleansing, natural disasters, famine or climate change - had necessitated the urgent movement of people, resources, aid, or materiel – in quantities, and at speeds never seen before.

A vast, redundant, and attritable “machine” of logistics, stretching within and in-between member states had to be adapted, enhanced, enlarged, or otherwise built from scratch. This “machine” could not be expected to operate from a cold start. It had to run idle in the background, continually transporting people, goods, and resources – operating at a loss if needed. The resilient social fabric as established in the previous tier of the “ziggurat” was to be the proverbial “sail” powering this mighty, globe-straddling “vessel”.

If and when the crisis came, it could rapidly deploy to act and transporting war-fighting forces was the last among its many options.

There was much work to be done, especially across the Pacific – linking new member states with those in the Old World and the Americas. Air and maritime shipping lanes were expanded and new series of rugged, low-cost airplanes and sea vessels were launched to populate them. In the civilian domain, the Alliance commissioned, or through private partnerships encouraged the development of affordable and robust personal cars, vans, and utility vehicles. These vehicles, sometimes unsightly but affectionately well-liked in all member states, were offered to the general populace at highly discounted rates. They lacked the fanciful digital augmentations that most private cars and trucks had at the time – but then again, they did not have planned obsolescence either. They did not use batteries, but their resourceful engines ran on any sort of fuel that could flow – be it biodiesel, ethanol, LPG gas, or good-old fossil fuels. Built out of the maximum number of interchangeable parts, they were rugged, reliable, and as long as they were maintained, could serve their owners for multiple generations.

In all great emergencies of the past, lowly civilian vehicles had contributed the most in evacuations, resupply operations, and even offensive actions. By ensuring that every society had access to fleets of low-cost, robust vehicles, the Alliance bolstered the backbone of its agile logistics network. Especially in Eurasia, this saturation gave it an edge in dealing with emergencies; natural or man-made.

This was not to say that all Alliance logistics advancements were in the civilian sphere. Member states built up widespread, survivable logistic networks for materiel and personnel across land, sea, and air, and embedded them in the rhizomic network of the aforementioned civilian infrastructures. Member states frequently conducted massive exercises to maintain their logistics readiness for any number of war, disaster, or famine-related scenarios.

MILITARY

Now let us study the apex of the NATO strategic pyramid. The robust logistic capabilities stretching across the Alliance, bolstered by social welfare and cohesion, was in essence a massive machine that could move vast numbers from one end of the globe to another. Military materiel and forces were but one of the options this network could choose to move in time of an emergency.

Many in the past had speculated that agile, smart, technical solutions would increasingly replace the heavy-duty warfighting elements that had dominated member states’ militaries during the First Cold War. The days of massed infantry, tanks, and large surface ships were thought to be limited. Smart missile systems, drones, and air-launched munitions were predicted to prevail.

A hypothetical visitor suddenly sent from the early 2020s to the Alliance’s 150th year, then, would be surprised by the eclectic mix of “old” and newfangled technologies in the militaries of the day.

Certainly, there were many technical advances – but these were by then so rugged, redundant and well-integrated that they were mostly invisible. Outside of the skies, there were few large and “flashy” pieces of military equipment, and even there, baroque and expensive systems were rare. A detailed exposition of military equipment dominating the battlefield of the 2090s would be too long for the scope of this essay – but suffice it to say that many platforms on air, sea, or land looked far less flamboyant than their legendary – and often overpriced and overtasked - precursors at the turn of the century. Mostly unmanned; built in attritable quantities; interoperable across control platforms and layered information networks; robust enough to be used in “dumb mode” if necessary; they were not quite “tools” – not quite “drones” – but constituted a sort of versatile, new, force-multiplying battlefield element in themselves. They possessed a certain dull concision in form, one held only by systems that worked. C4I (Command, Control, Communication, Computing and Intelligence) systems were as thoroughly integrated into these elements as carbon was into the metabolisms of living beings.

In the presence of these new elements, however, much looked the same. Infantry specialisations still constituted the core of military action, and there were as many men (and women) as drones, smart tools, and vehicles on the battlefield. One remarkable addition was the presence of multiple “gamers” – usually-helmet-wearing controllers of flying, crawling, swimming, or burrowing platforms at squad and section level. These smart and high-strung individuals performed great deeds of heroism on the battlefield, controlling their systems while crouching in fetal position in mud-filled trenches. One of the most popular video dramas of the decade even centred on the tragic story of two such “gamers”, lovers in the time before their countries’ dissolution, illicitly exchanging passionate messages during the day; and being forced to hunt each other with nocturnal “owl” drones across opposing trenches at night...

Aside from this, there was an emphasis on increased mobility through mechanisation – but most mechanised elements had by then given up on armour – pointless in the face of pervasive autonomous munitions – and a new class of semi-autonomous, trackless, heavily armed, but lightly armoured fighting vehicles had replaced main battle tanks.

In the skies, a tangled ecosystem of loitering munitions, master-slave control nodes, attack drones, drone-hunters, “counter-hawks”, and dedicated local EWF vehicles had evolved. Their sizes ranged from very large, stratospheric observation platforms to bat-sized autonomous bomblets used in the infamous “Project X-Ray” family of smart munitions. Once more, skilled and courageous operators guided most of these vehicles, but others also flew and hunted of their own...

CONCLUSION

This, then, was the overall form of the Alliance as the world prepared to enter the 22nd Century. Faced with pervasive challenges targeting the social stability of its member countries, it had changed from a purely military alliance to a shared cultural entity, ensuring the well-being of its member states, able to coordinate the greatest logistic actions in human history, and ready to strike with a resilient mix of forces.

No alliance in history had done more to prevent war, and thus, no alliance had done more for the welfare of human life on the planet. To defend and sustain its member states, NATO had become more than a mere military bloc – it was now an Alliance of Societies.

***

Copyright laws protect all content associated with this site.

Contact c.m.kosemen@gmail.com for inquiries.

***